Killing Cousins: The long history of Russo-Ukrainian tensions

The borders of Soviet Ukraine 1917-1928. Many parts of present day Ukraine were added later in the Soviet period.

Hellerick, CC BY-SA 4.0

“Why does

a boot

crush the Earth — fissured and rough?

What is above the battles’ sky –

Freedom?

God?

Money!

When will you stand to your full height,

you,

giving them your life?

When will you hurl a question to their faces:

Why are we fighting?”

— Vladimir Mayakovsky, Call to account! (1917)

Vladimir Mayakovsky, widely considered among the greatest Russian poets, always boasted of his mixed heritage; he was proud to be the child of a Cossack father and a Ukrainian mother. Like many in the early Soviet period he hoped that the October revolution of 1917 would mark the beginning of the end for conflict between nations, yet here we are in another century and once again, Mayakovsky’s homeland finds itself in another war.

Putin is lying: Lenin didn’t invent Ukraine, Ukrainians did!

Russian President Vladimir Putin invaded Ukraine on Feb. 24 and claimed Ukraine as “historical Russian land.” He said the Ukrainian national identity was created by Bolshevik Russia and Vladimir Lenin in particular. However, is there any truth to this?

Russians and Ukrainians share a common history (as do Belarusians and Rusyns/ Southern Ruthenians) with the hybridization of Norse and Slavic culture in what historians call the “Kievan Rus.” This political entity spread eastern Slavic culture throughout the region, with the descendants of these “Rus-ians” only starting to identify themselves as distinct nations in early modern times.

The origin of the name “Ukraine” is controversial, but the dominant theory is that it means “borderland,” while some prefer “homeland.” In the Tsarist period, the diminutive name “Malorussy” (little Russians) was used for inhabitants of the region, but most seem to have continued to call themselves “Rus” or “Rusyns.”

All Tsars claimed to be the rulers of “All of the Russias,” but the people we know as modern Russians became the dominant ethnic group during the Tsarist period. Over time, residents of Ukraine came to see themselves as a distinct people, and a rural peasant nation, dominated by their imperial “Great Russian” cousins. Starting in the 1700s the Tsarist regime attempted to enforce the Russification of Ukrainians, along with other subjugated peoples of the empire.

How does Vladimir Lenin fit into this? When the February revolution overthrew the Tsar, the new government continued Russian involvement in World War I. The provisional government debated Ukrainian autonomy, but the issue was not resolved, leading to a split in the provisional government and the rise of Minister-President Alexander Kerensky. Kerensky nominally supported Ukrainian autonomy, but delayed it to focus on the war effort.

Lenin and the Bolsheviks believed the world war to be an imperialist conflict fought for profit, and the domination of small nations and colonial peoples. The Bolsheviks demanded a “democratic peace” with the right to self-determination for all nations, including those of the former Russian empire. Speaking of Ukraine, Lenin argued for unconditional defense of its right to self-determination:

“Accursed tsarism made the Great Russians executioners of the Ukrainian people, and fomented in them a hatred for those who even forbade Ukrainian children to speak and study in their native tongue […] Russia’s revolutionary democrats, if they want to be truly revolutionary and truly democratic, must break with that past […]”

Does this mean then, that Putin is correct in naming Lenin as the architect of Ukrainian nationhood? No. For Lenin the point was not that it was inherently good for Ukraine to separate itself from Russia, but that any kind of democratic union requires giving oppressed people a choice between unity and independence. According to Lenin:

“We are opposed to national enmity and discord, to national exclusiveness. We are internationalists. We stand for the close union and the complete amalgamation of the workers and peasants of all nations in a single world Soviet republic. … Consequently, we Great-Russian Communists must repress with the utmost severity the slightest manifestation in our midst of Great-Russian nationalism.”

Lenin had a major impact on the destiny of Ukraine, but he should not be attributed as its creator. Instead, Lenin recognized Ukraine’s national awakening and argued that respect for self-determination would create a path toward greater unity. Lenin continued to argue for this until his death, arguing that the Soviet Union should be a block of equal republics (with full language rights) voluntarily united as a “Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.”

Whatever Lenin’s wishes, the Soviet Union did not abolish conflict between nations. Stalin reversed “nativization” policies promoted by Lenin, and aspects of Russian culture were once again enforced on the USSR’s national minorities.

The Great Famine of 1932-1933, the nationalist backlash.

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, the USSR enacted forced collectivization, which resulted in fierce resistance from peasants and widespread famine in 1932-1933. Ukraine, a heavily agrarian region, was hit especially hard by the famine. The events of this period are perhaps some of the most hotly debated in Soviet history. Ukrainian nationalists (and many western governments) take the position that Stalin created the famine, a genocide known as “Holodomor,” to destroy the Ukrainian nation.

Most scholars have framed the famine as bureaucratic incompetence that didn’t specifically target Ukrainians for starvation, but also didn’t take action to prevent their deaths. The USSR also continued to appropriate grain while masses of people starved.

Others, such as historian Anne Applebaum in Red Famine, acknowledge that Stalin did not intend to kill Ukrainians, but that the impact of the famine combined with the policy of Russification may not legally constitute genocide due to lack of intent, but that it is still comparable to genocide in a moral sense.

Regardless of where one stands on “Holodomor,” the famine of 1932 and 1933 was a disaster for Ukraine. It helped to spark anti-Soviet and national separatist sentiment, especially after the USSR seized parts of eastern Poland, with some areas being annexed by the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. The newly annexed West Ukrainians had pre-existing political traditions, and nationalistic convictions, which were now introduced to an eastern Ukrainian population freshly shaken by mass starvation, and political purges.

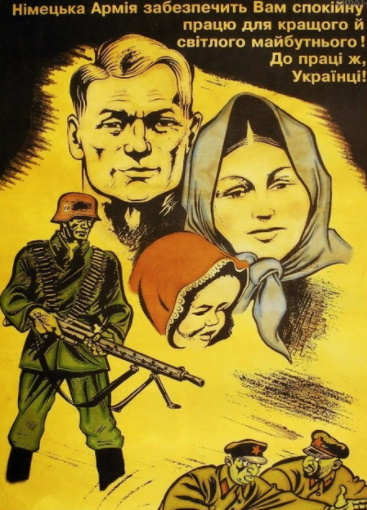

During World War II Ukrainian nationalists rose up against the Soviets. Fascist organizations like the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists and Ukrainian Insurgent Army allied with Nazi Germany and participated in the Holocaust, murdering Jews, ethnic Russians, left-wing Ukrainians and other national minorities.

Today, both the famine and the consequences of Ukrainian uprisings during World War II loom large over modern Ukrainian politics. Soviet policy toward Ukraine repeatedly zig-zagged between repression and promotion of national culture. In 1954 the government of Nikita Khrushchev transferred control of the Crimean peninsula to the Ukrainian SSR despite Ukrainians only being a minority of its population.

After Independence: A divided country.

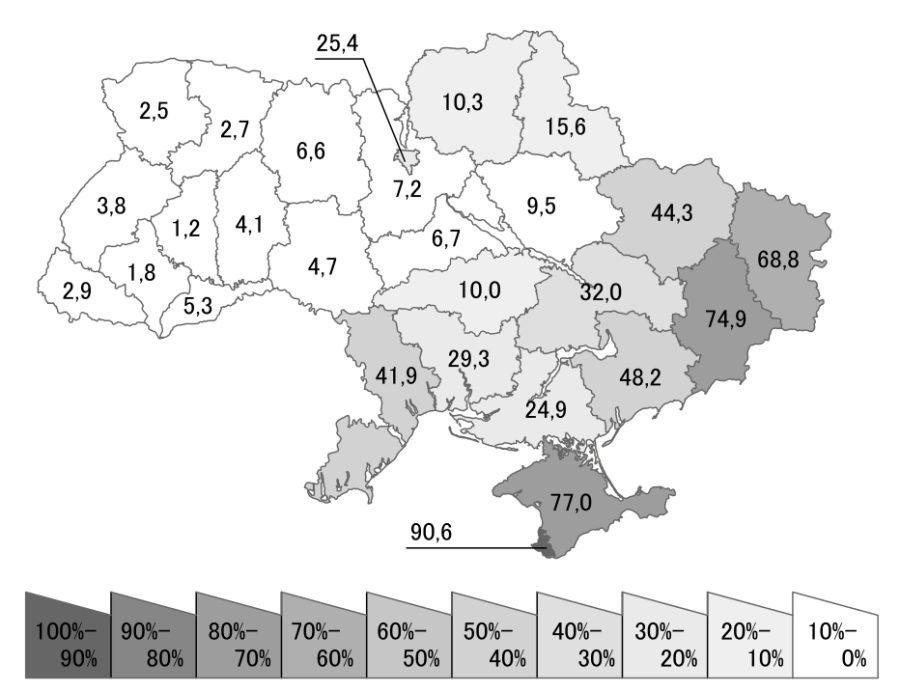

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Ukraine was left with ⅓ of its population speaking Russian as a first language, and with its political and economic interests divided between Russia and the West. Like in many former Soviet Republics the economy of Ukraine has been largely dominated by “Oligarchs,” people who had come to own privatized state property through often corrupt deals.

Some sections of this oligarchy have economic interest in ties to Russia, while others have sought integration with the European Union and the NATO alliance. The political history of independent Ukraine has been one of alternation between Russian-aligned and western-aligned political blocs.

The 2004 “Orange Revolution” protests broke out in response to claimed electoral fraud by pro-Russian sectors of the government to rig the elections in favor of former Prime Minister Viktor Yanukovych. These protests led to a rerun election in which Yanukovych lost to pro-western candidate Viktor Yushchenko.

This administration, while initially popular, quickly fell into in-fighting and in the next election Yuschenko lost to Viktor Yanukovych by a landslide. One of his last acts as president was to name Ukrainian Nazi collaborator Stepan Bandera as a “Hero of Ukraine,” an act annulled by the following administration.

Yanukovych tried to walk a fine line between pro-western and pro-eastern factions of Ukrainian society, declaring his wish that Ukraine remain neutral militarily, while pursuing good relations with Russia as well as integration with Europe.

In late 2013, Yanukovych rejected an agreement that would have led to closer relations with the European Union, and instead signed an agreement with Russia, leading to protests in Kiev’s Independence Square. These protests became known as “Euromaidan” (Maidan is Ukrainian for “square”), and led to the overthrow of Yanukovych’s administration. These protests received firm backing from the U.S. and other western powers, with some of the leading figures and organizations having received large amounts of money from USAID.

Pro-Euromaidan protests, mostly in the West, were matched by “Anti-Maidan” protests in the southern and eastern parts of the country. Polling at the time showed the country was almost evenly split.

Violent clashes happened across the country between pro-Maidan forces, anti-Maidan forces, and the police. By February-March 2014 these clashes had devolved into civil war, with far-right militias and the Ukrainian military fighting separatist militias, with Russia and their proxies playing an increasingly large role over time. On March 18, the Russian federation officially annexed Crimea, a territory it had occupied since late February.

An election was held in conditions of civil war that excluded several separatist regions, and under conditions of paramilitary violence against opponents of Euromaidan. This returned a landslide victory for oligarch Petro Poroshenko, an outspoken nationalist who vowed to “wipe terrorists off the street.” This promise was bolstered by massive amounts of military and logistical aid from the U.S. and other NATO countries.

Poroshenko’s administration carried out many controversial actions, such as incorporating the neo-Nazi Azov Battalion into the National Guard, passing sweeping “decommunization” laws that restricted political speech, restrictions on the use of the Russian language and the banning of left-wing political parties. The “Anti-Terrorist operation” of Poroshenko’s administration led to intensification of military actions in eastern Ukraine that included human rights abuses. One of the last acts of Poroshenko’s administration was the granting of veteran status and pensions to former members of Ukrainian fascist paramilitaries from World War II.

In this tense environment a new hope appeared on the horizon for many Ukrainians: Volodymyr Zelenskyy, a popular comedian of Jewish descent who grew up in a Russian speaking community. Despite the 2019 election being marred by Nazi interference at polling places Zelenskyy managed to sweep to victory over the more extreme candidates on a platform of peace in eastern Ukraine, a loosening of the Poroshenko-era ban on the Russian language, and attempts to regularize relations with Russia, while also promoting integration with the European Union.

Despite these promises, very little changed in actual policy. Policies promoted by the previous administration have remained almost entirely unchanged, and the extreme right was free to expand, while receiving training from the CIA. Zelenskyy may or may not have the most sincere of intentions, but it is not him who rules the country, but the western-aligned section of the oligarchy, eager for spoils and the elimination of their Russian-aligned rivals.

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est Pro patria mori.

Акутагава, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Putin’s invasion has nothing to do with freedom of eastern Ukrainians or the “denazification” of the country. It is a manifestation of old fashioned imperialism and Russian nationalism. NATO’s intervention in Ukraine has not been about freedom of Ukrainians from Russian oppression, but imperialism, an attempt to surround and isolate its Russian rival. Ukraine is not a democracy today, and never has been because it has never been free from interference from Russia, or the west. It has been dominated by foreign powers, and their oligarchic allies.

Mass protests in Russia have shown that everyday Russians are not simply standing by and letting Russian imperialism push around Ukrainians. Are we ready to do the same, and to join with our friends in Russia, Ukraine, and in the People’s Republics to demand that our own governments stop using Ukraine as a pawn?

In the midst of World War I it was another Ukrainian, Alexandra Kollontai, who wrote:

“I know now that it is not you who are my enemy. Give me your hand, comrade! We are both of us the victims of deception and violence. Our main and common enemy is at our rear. […] let us cleanse our homelands from the real enemies of the people, from the tsars, kings and emperors! And when power is in our hands, we will conclude our own peace.”

Christopher Hill can be reached at [email protected].

Christopher Hill is a member of the U.S. Section of the IMT and the Chico Democratic Socialists of America. This article should not be taken to represent the position of either organization.

Anastasia // Mar 13, 2022 at 9:50 am

Spot on article!

Now more than ever it’s important for us to read and understand Lenin when he discussed revolutionary defeatism. This goes for people here in Russia, where it seems about half of Russian Marxists believe this “denazification” story; hook, line, and sinker. And how could they not? Many Russians are swept away by the fantasy of saving the world from fascism, and they take half of Western Marxists with them, whose brains are doped up on Marvel format morals; that there is always a good guy to be found in a war. There HAS to be! Reality is grim and many choose to close their eyes.

Now, these two parties who saunter about defeating Nazis in Ukraine are a danger, but the biggest one are liberals that wear their emotions on their sleeves and believe that if America punishes Russian working class enough, somehow they will develop Stockholm Syndrome and find this inspirational enough to overthrow Putin. Because that’s how it’s worked every other time US did that, right? Right? Instead, we are seeing Russians who became unemployed by the tens of thousands overnight in a country that has little social safety nets. Putin and his government are trying to fix this by nationalizing some industries. Thus, winning the trust of Russians who were at one point on the fence or against the war.

In a time we should be saying the “enemy is at home!”, we have collectively decided to pander to a Cold War Era tactic, like sacrificial sheep looking for the US media to lead us to the slaughterhouse.

Only when we decide to stop playing the abusive games of the ruling class and unite as one against NATO and Putin, can we see through gaslighting attempts to keep the war machine rolling. Under no circumstance should we accept the conditions of any war but class war. No ifs, ands, or buts about noble sanctions. Under no condition can sanctions accomplish their goal in the hands of number one war machine in all of human history. Sanctions work as well as punitive style justice dealt out to petty crimes, which is not at all.

Ones feelings of hopelessness and helplessness in the face of a terrible war does not give one the right to endorse the bigger imperialist to take out the weaker imperialist, where the working class is the only collateral on all sides.

Semyon // Mar 3, 2022 at 8:45 am

НЕТ ВОЙНЕ МЕЖДУ НАРОДАМИ! НЕТ МИРУ МЕЖДУ КЛАССАМИ!

chill3 // Mar 6, 2022 at 10:52 pm

ні війни між народами, ні миру між класами