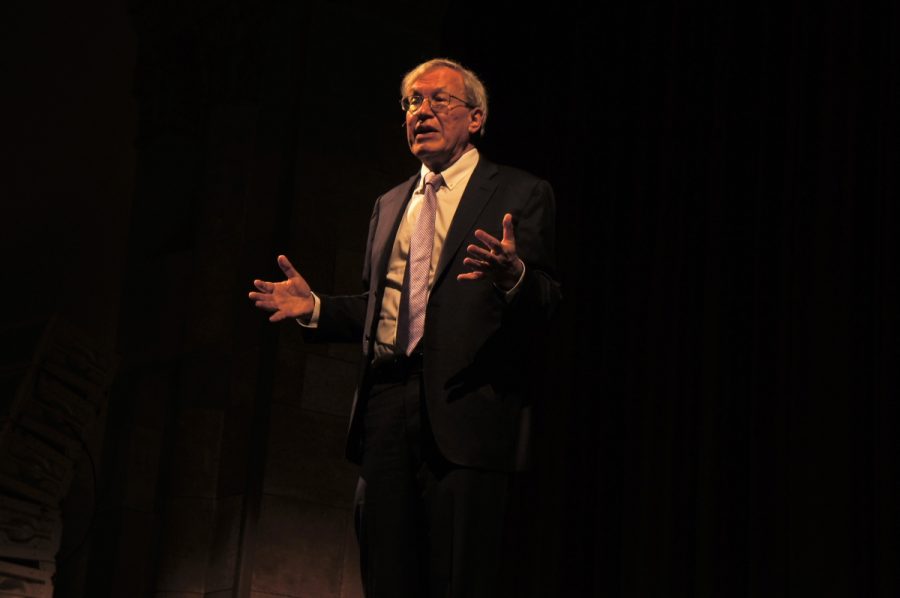

To a nearly full Laxson Audiorium, Erwin Chemerinsky, Dean of UC Berkeley’s School of Law, and nationally-renowned First Amendment scholar, spoke Thursday evening, about the importance of free speech on college campuses, the precedents that have been set, and the push back against it.

According to Diana Dwyre, professor of political science at Chico State, he was a favorite when choosing who would speak for Constitution Day.

“Every generation thinks it’s the first to discover the issue of free speech on college campuses,” Chemerinsky said, “but the reality is that the controversies about this are about as old as colleges and universities.”

The image he brought up, what he believes most people see when they think of free speech issues on campus, the free speech movement that happened in Berkeley in the mid-1960s. He also showed how times have changed since then. Instead of going against the administration for free speech on college campuses, the current issue is outsiders wanting to come to campus and speak.

When Milo Yiannopoulos came to UC Berkeley’s campus last year, it cost UC Berkeley $100,000 in damages from protesting against his arrival. In that same year, Ben Shapiro came to Berkeley and cost the school $600,000.

He then got into the principle of free speech.

His first principle is that all ideas can be expressed on a college campus, no matter how offensive. The Supreme Court has said all ideas, even those that people would consider the most offensive, are protected under the first amendment.

In 1969, in Brandenburg vs Ohio, the Supreme Court ruled that a Ku Klux Klan member’s speech was protected. In 1992, the court ruled that speech can’t be criminalized because of its content Chemerinsky such past precedent’s with the crowd.

His second principle was that free speech isn’t absolute.

The first amendment doesn’t protect, for example, child pornography, false advertisement, incitement of illegal activity, or harassment.

His third principle was that college universities can have time, place, and manner restrictions regarding speech, so long as they have adequate opportunities for communication.

“The government is able to regulate the manner of the expression,” Chemerinsky said. “There’s a first amendment right to use public streets for expression, but that doesn’t mean there’s a first amendment right to block public freeways during rush hour.”

From Aug. 27 to Sept. 27, UC Berkley spent almost $4 million on security fees, according to documents the school released.

His final point was the problem of not giving a platform to speakers. Students might engage in speech to prevent anyone from hearing someone speak.

He gave an example from the University of Oregon where the campus president, Michael H. Schill, was interrupted by students that chanted so loud he couldn’t be heard.

The talk wrapped up with a question and answer portion where many students and people from the community spoke. Ayoub Dhaovud is a high school exchange student that goes to Inspire School of Arts and Sciences who asked Chemerinsky where the line is between free speech, and speech that poses direct threats on individuals or groups.

“Hate speech doesn’t have a line, but the other is prosecutable by law,” Dhaovud said. “I don’t think there should be a line. Even when it comes to threats, we never know if they’re truthful or not.”

Many people agreed with what Chemerinsky had to say, including Andy Potter, an assistant professor of political science, and Michael L.W. Swindle, a graduate student at Chico State.

“I consider myself an advocate of free speech,” Swindle said. “When it comes to a public forum: if allowing some bigot to speak hatefully on a podium allows me the right to dissent against a government policy that’s unfair to minorities, it’s a fair trade.”

“Free speech is arguably the bedrock in which our other civil liberties rest,” Potter said.