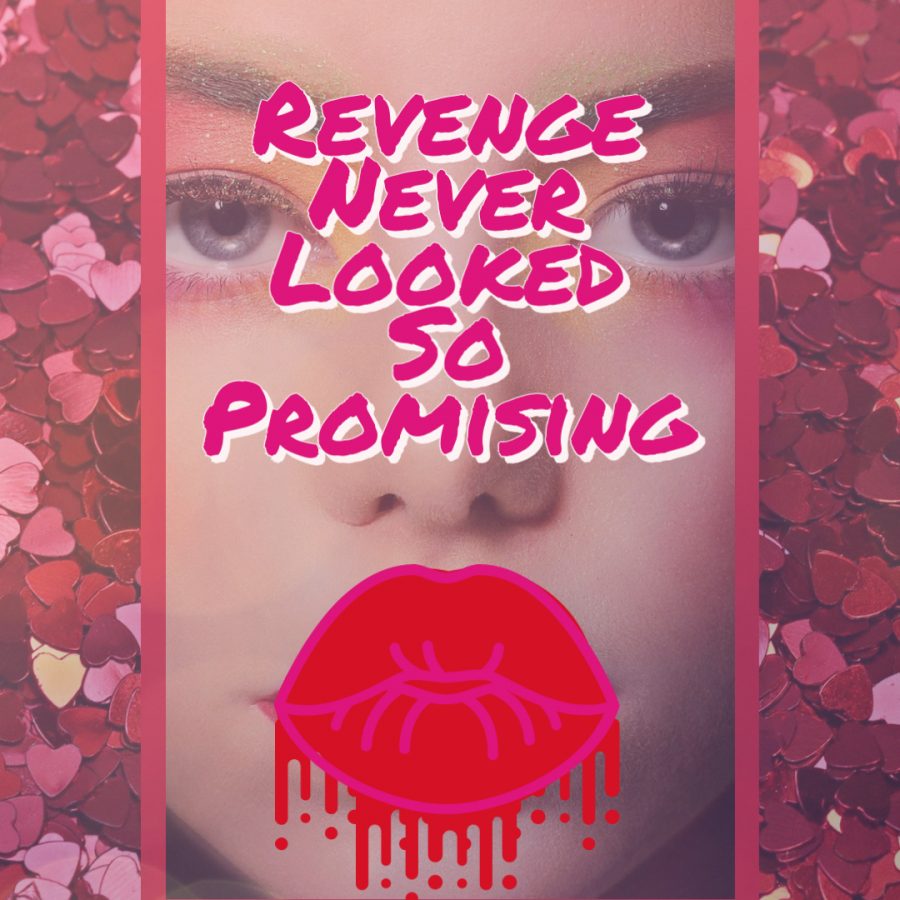

From the beginning, “Promising Young Woman,” doesn’t hide from its leading theme: the complicity of society in rape culture. It hides the gruesome reality of the female experience with a traditional “girly” pink-colored, flower-drenched and confectionary dream-like aesthetic.

It uses this imagery to highlight gender power dynamics: The power imbalance we institutionalize when we always think about promising young men and their future potential, but not women who had sexual violence forced upon them.

The film centers on the character Cassandra, also known as Cassie, who is unable to get past the rape and death of her best friend Nina, who died while they were in medical school. Nina’s assault was swept under the rug by everyone from students and friends to the schools’ faculty, all in an attempt to hide the gritty reality of rape.

In order to keep the world looking clean and pristine they cover up the incident with a shiny varnish, making everything look like a glossy perfect picture. Everyone else could forget, but not Nina or Cassie.

Rape can often be a traumatic experience that leaves victims with long-lasting affects, especially regarding how they are treated by others after reporting their rape. “Promising Young Woman” focuses its narrative on the lasting effects that sexual violence toward women can have on victims and their friends and family, also know as secondary victims of rape. We follow Cassie as the secondary victim of rape and how this event that happened to Nina affects her life.

Having dropped out of medical school, Cassie works at a coffee shop during the day. She spends her nights acting drunk at different bars, exacting her catharsis on men who take advantage of her assumed vulnerable state. These “nice guys” will not be the only people she obsessively exacts revenge upon. She goes after all the people who were complicit in Nina’s assault, whether it was a fellow female classmate or the dean of the medical school she attended.

The LA Times interviewed writer-director Emerald Fennell, a 35-year-old UK filmmaker who explained some of the themes represented in her film. “The thing that interests me so much and was so kind of enjoyable examining in this film was that we are all living in dread of being discovered as being bad people,” Fennell said. “ That’s a human thing, it doesn’t matter what the context is, who it is. Everyone wakes up every day thinking they’re good.”

In this film, every man that is confronted about their thinly-veiled misogynistic behavior is baffled by the accusation. They have entrenched themselves in myths about rape, myths that society perpetuates. Their aggression, both violent and sexual, are seen as natural traits.

This anger from men is met head-on by the poppy, feminine aesthetic that surrounds Cassie’s universe. “I think often they’re dismissed, those sorts of things,” Fennell told The LA Times. “And so I wanted to be like: ‘Just because a girl looks like this does not mean she isn’t holding a world of terror and rage inside her.’”

Even Cassie is not immune to outward aggression. In one scene, she smashes the windshield of a man’s truck when he bearates her for idling at an intersection for too long. All her rage and pent-up emotions spill out in a random act of violence toward a complete stranger.

It would be foolish of us not to discuss how the sexual assault occured in an academic setting in this film. The perpetrators and the victim of the rape are college students and those that turn a blind eye are fellow students and faculty.

This blind eye mentality is not just found in PYW, but also in the documentary “The Hunting Ground,” which explores the epidemic of sexual assault on college campuses. One of the unnerving statistics that come out of this documentary is that one in five college women, and one in 33 college men, will be sexually assaulted during their time in college. That adds up to an estimated 100,000 assaults in one year, but only 5% of these get reported.

This documentary also reports that men in fraternities are three times more likely than other men to commit rape. This poses the question: Why do we keep fraternities around if they are so damaging to a large percentage of other students? Finance factors play a role — about 60% of fraternities have alumni that give donations to the college.

The film also provides statistics that indicate that athletes are involved in a higher-than-average number of assaults and, like fraternities, big-time sports are moneymakers. The need for profit overshadows colleges’ initiative from doing anything profound to help stop this epidemic; they are a complicit institution that our society values.

Colleges and universities are so determined to protect their reputations, they fear that acknowledgment of the problem will destroy their brand and business. What does it say to young women and men when an institution chooses profit over student safety and well-being?

When an institution that’s accepted your hefty fee dismisses and invalidates your trauma, how do you move on from the event? How do you not relive the experience every time you happen to see your attacker on campus?

PYW perfectlyreminds us that rape culture isn’t just a plot point in a film; it is a dilemma entrenched within our culture. It reminds us that this is neither the first nor last time we as a society have been complicit in acts of sexual violence against women.

The Brock Turner case, the 2012 Steubenville high school gang rape and the Daisy Coleman story all had a hand in creating PYW. All are traumatic, gruesome crimes of violence where the victim’s alcohol level was of more concern than the sexual violation.

Talking about rape isn’t fun and makes many of us feel uncomfortable, but shying away from the topic is it’s own form of complicity. When we choose not to speak about an issue that affects, on average, 433,648 American victims (age 12+) each year, we have chosen complicity.

This is where PYW shines because it takes a topic we don’t like to speak of and makes it strangely funny, adrenaline-filled and thought-provoking. It engages us, asking us to enjoy the film until we feel the sickening shiver down our spines.

A complexly interweaved spiderweb of complicity exists in our society when we talk about rape and rape culture. It doesn’t favor one gender over another. Rather, it shows how we have developed a culture of avoidance and victim blaming in an attempt to distance ourselves from the taboo word “rape.”

Elaine Hatfield, an American psychologist at the University of Hawaii, suggests that we victim blame as a desperate attempt to assign blame. The human brain endeavors to make the act of rape controllable or avoidable, allowing us to protect ourselves.

If we can identify a reason for this violent act to take place, we can simply not do the “one thing” that caused it to happen. We become complicit when we try to avoid the reality that rape can happen to anyone. It’s because we’ve built a society where rape is ingrained in how we see gender dynamics and power.

This film makes us all — no matter what gender — take a look at ourselves. It forces a mirror to our faces, making us confront the moments when we wrongly blamed the victim, citing the all-too-often used fallacious phrase of “she was asking for it” or the victim blaming narrative of “maybe you shouldn’t have gotten so drunk.”

“Promising Young Woman” is asking us to swallow a bitter pill that acknowledges our complicity in oppressive power structures. We dry swallow this pill, feeling it slowly slide down our throats, so we can have an honest conversation about sexual violence and rape culture.

Erin Holve can be reached at orionmanagingeditor@gmail.com and @Erin_Holve on Twitter.

Rape, rape culture, promising young woman, movie, complicity, victim blaming, colleges, universities