“We are sons of the Mexican Revolution, a revolution of the poor seeking bread and justice. Our revolution will not be armed, but we want the existing social order to dissolve; we want a new social order. […] The time has come for the liberation of the poor farm workers.”

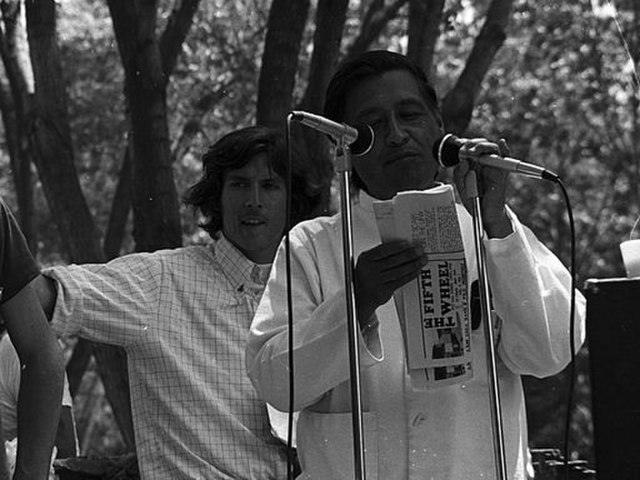

Cesar Chavez, Plan of Delano

Cesar Chavez day has been celebrated as a national holiday since 2014, but many people have misconceptions about what he did and believed. At best Chavez is commonly stereotyped as the “Mexican Martin Luther King Jr.” Cesar Chavez played an important role in fighting for the rights of Chicanos but his legacy contains much more, and is much more complicated than his status as a secular saint might lead us to believe — what is the real significance of the man who called himself the leader of the “non-violent Viet Cong?”

Born in Yuma, Arizona, in 1927 to a relatively well-off Mexican immigrant family (his grandfather owned a business and farmland, and had helped his extended family to immigrate), a young Chavez moved to California after his family lost their land amidst the Great Depression.

The family settled in San Jose, where Chavez would become a farm worker after completing a junior high level education. After a brief stint in the U.S. Navy Chavez threw himself into his farm-working career, and alongside it labor and political organizing.

After initially working for the Community Service Organization and the National Farm Labor Union, in 1963 Cesar Chavez joined with CSO colleague Dolores Huerta. Together they founded the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) to organize Mexican American agricultural workers in Kern County and the surrounding area.

The NFWA wasn’t initially a labor union: Chavez and Huerta looked to a model that had grown out of the Mexican labor movement, and had been brought along by immigrant workers — the “Mutualista” — an organization based around mutual aid and providing a social safety net and sense of community for workers, rather than directly fighting for better working conditions and changes in the workplace.

Despite this original focus, the NFWA eventually took the path of direct, on-the-job organizing, and was not the first Mutualista to do so. According to Justin Akers-Chacón, a scholar on the Mexican-American labor movement:

“These labor mutualistas primarily grouped the working class together and became remarkably adaptable in response to class needs, converting into quasi–labor unions and strike organizers under conditions of class struggle […] opening their halls for meetings, joining pickets and supporting campaigns.”

Southern California’s agricultural labor force was heavily divided during the 1960s. Mexican American workers and non-citizen Braceros dominated in some parts of the industry, while others had a primarily Filipino and Filipino American workforces. In times of labor discontent this disunity was often made use of, with workers of different ethnicities being played off each other in order to break organizing drives and strikes.

In September of 1965, the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), a mostly Filipino and Filipino American labor organization, launched a strike against Delano grape growers in response to being offered less than the minimum wage.

AWOC organizers Larry Itliong, Ben Hines and Pete Manuel asked for a meeting with Chavez, and shortly thereafter, tense conversations were able to convince him of the need for class unity against the growers. On September 16,1965, the NFWA joined the AWOC on strike — the beginning of a campaign that lasted for five years before achieving victory, and would see the transformation of the NFWA and AWOC into a unified, multi-racial trade union and AFL-CIO affiliate — the United Farm Workers (UFW).

Despite his initial reluctance to join the strike, Chavez played a major role in its leadership and the campaign led to his widespread public identification as a major figure in the labor movement, and proponent for the rights of Mexican Americans.

Chavez was far from the first Latino-American to play a significant role in the labor movement. He was standing on the shoulders of giants like Emma Tenayuca, Luisa Moreno, Bert Corona, Ricardo Flores Magón and countless Wobblies, both known and unknown, who organized the fields of California before World War I. In the “Plan de Delano,” its name referencing many such “plans” that were integral to the Mexican revolution, Chavez explicitly claims this heritage for the Delano strike and Mexican-American workers:

“It is clearly evident that our path travels through a valley well known to all Mexican farm workers. We know all of these towns of Delano, Madera, Fresno, Modesto, Stockton and Sacramento, because along this very same road, in this very same valley, the Mexican race has sacrificed itself for the last hundred years. Our sweat and our blood have fallen on this land to make other men rich.”

What made Chavez so significant is that he advocated non-violent, yet militant tactics during a period in which the labor movement had suffered numerous defeats, and where “business unionism” had led to gains for better-off white workers, but had left poorer workers — especially workers of color — behind.

Cesar Chavez, Plan of Delano

“The strength of the poor is also in union. We know that the poverty of the Mexican or Filipino worker In California is the same as that of all farm workers across the country, the Negroes and poor whites, the Puerto Ricans, Japanese, and Arabians; in short, all of the races that comprise the oppressed minorities of the United States.”

Chavez and other UFW organizers waged a public campaign that eschewed backroom dealing in favor of direct, on-the-ground labor stoppages, consumer boycotts and the organization of solidarity both within and beyond the directly affected communities. The mass organizing of the UFW made the struggle of farmworkers something that people could directly connect to their dinner table, and feel the power to impact by supporting the labor boycott.

Mass demonstrations helped to build connections with other movements. The rising movement of Chicanismo among Mexican American youth drew inspiration from the UFW struggle, and appropriated some of its imagery. Chavez rallied against the Vietnam War, and in favor of gay rights, at a time when it was uncommon. Chavez even threw his lot in with the animal rights movement, adopting a vegetarian diet out of sympathy for animals.

Chavez deserves remembrance and praise for his many accomplishments, but this does not mean that he does not deserve criticism.

A major blemish on the legacy of both Chavez and the UFW is that their idea of working-class unity and solidarity did not extend to undocumented immigrants. The United Farm Workers in Chavez’s time opposed policies allowing immigrant workers to enter the United States, and infamously set up a tent barricade along the U.S.-Mexico border to prevent undocumented people from crossing into the United States. The UFW claimed this was action against “scabs” rather than against immigrants as such, but the UFW has since apologized for its role, and has taken a very different position after Chavez’s death.

Chavez also had authoritarian tendencies in his leadership style that led to a massive contraction of the organization in the late 1970s and 1980s. Inspired by the Synanon new-religious movement, Chavez implemented a practice known as “The Game,” which subjected members to purges, as well as intrusive and abusive practices. Chavez also led the UFW away from its core focus on organizing farm workers, and towards his own pet project of building a commune based on Catholic social teachings.

Chavez was a flawed human being, as are all human beings. We can take what is positive from his legacy, while leaving the rest behind — to fight for a world without poverty and discrimination. Sí, se puede!

Christopher Hill can be reached at orionmanagingeditor@gmail.com.

Joel Levine via Creative Commons Attribution 3.0