Hidden in a meeting room on the Bell Memorial Union’s third floor is a mural that many students have likely never seen before. Dedicated for Cinco de Mayo in 1995, the mural memorializes the struggles of Chicanos for equality in the United States, and their connection to and appreciation of the pre-Colonial past of the Americas.

Muralist Javier Barajas Villanueva was born Aug. 26, 1951 in the city of León, Guanajuato, to a Mexican father and a Chicana mother from Richmond, California.

The people of Guanajuato have a long history of resistance to oppression and foreign domination. The nomadic Chichimecas of the region resisted both Aztec and Spanish occupation. Unable to force the Chichimecas into bondage, the Spanish brought enslaved Africans to work the mines and farms of the region.

Some of these enslaved Africans sided with the indigenous people in a 40-year guerilla war against the Spanish. On Sept. 16, 1810 dissident priest Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla gave the famous “Cry of Dolores,” launching the Mexican War of Independence. The poet and journalist Práxedis Guerrero, a martyred leader of the 1910 Mexican Revolution, was born in a small town near León.

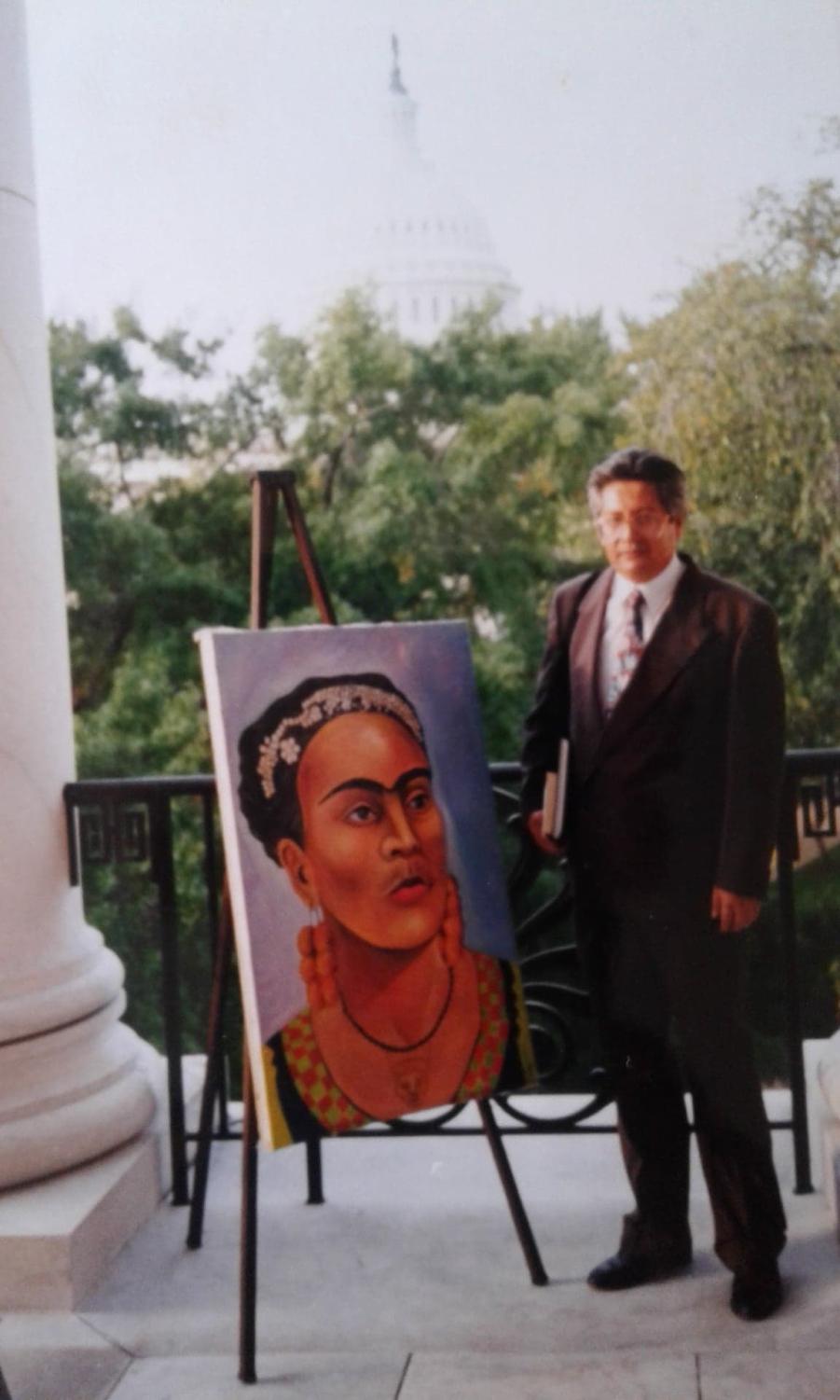

In 1993 a visitor who worked for Princeton University met Barajas in Guanajuato, and impressed with his work, landed him a position in their first, annual Artist in Residency program. The next year Barajas facilitated a show and lecture at the Library of Congress on the work of Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo. Oscar de La Torre, president of the Chico State Associated Students, saw his work at this time and contracted him to paint a mural at Chico State.

In honor of Cinco de Mayo we reached out to Javier to discuss the meaning of his mural on our campus, his influences and the lessons he has learned from his long career.

Q: How did you end up working on a mural in Chico?

A: I was invited by [Associated Students President] Oscar de la Torre. He told me that they needed a large painting dedicated to the memory of César Chávez. When I received the order I concentrated on the idea of creating a design: a leader, beloved for his struggle for the benefit of agricultural workers and their rights in the area of California. Love for Chicano cultural symbols, identity and defense of being Mexican-American.

Mexico is the Motherland. Its pre-Hispanic culture and anthropology gives them [Mexicans] strength as they walk on territory that was, in times past, that of their ancestors. Footprints mark the road south to north and vice-versa, so that is what frames the mural. It represents migration following the harvest. From the diverse kinds of fruits and vegetables, to the representation of the Code of Aztlán, it shows us where our roots come from.

[We descend from] Native People [who were] deeply linked with the land and study of the universe, of how stars influence sowing and Mother Nature herself. It’s day and night. It [the theme of the painting] is simply a synthesis, an allegory to César Chávez and the Statue of Liberty, which is in New York. To be Chicano is to feel pride in our identity in our country, the USA. No one, not even Mexicans themselves and Americans have such deeply rooted feelings of permanence.

Q: Your work seems to be heavily influenced by 20th century Mexican muralism, Diego Rivera in particular. How did you end up involved in this type of art, and why do you think the muralist tradition has had such a long-lasting impact on Mexican and Chicano artists?

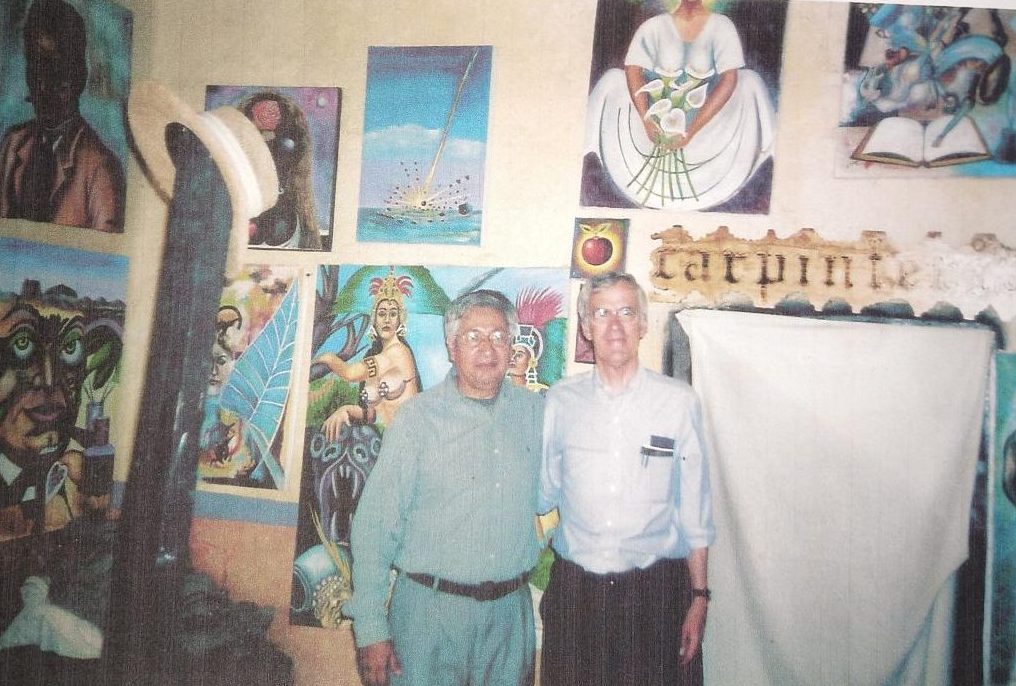

A: In 1986 I was invited by the director of Rivera’s museum in Guanajuato. I had been the president of a statewide painter’s association and wanted to do a collective expo with the most active artists in the state. It was in celebration of 100 years of its formation on Pósitos street. It was also taken to the city of León, to the House of Culture.

I identify as the people’s painter, as did the engraver Guadalupe Posada. He was the engraving instructor at the high school in León.

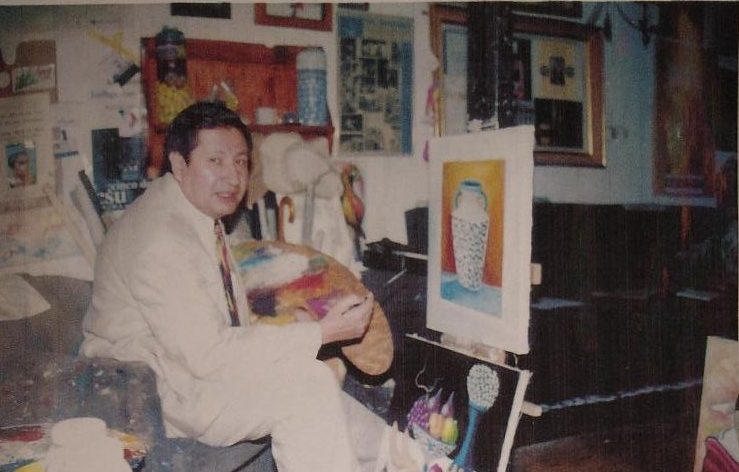

When I did my first exhibition, at age 22, I had an accident and injured my left leg. I got gangrene. I was in a coma and paralyzed but managed to recover. I painted about 100 pictures in the next three months as therapy after surviving, and I promised to dedicate my life to art. I began trips to study where the great works of muralists Diego Rivera, Siquieros, Orozco, Tamayo as well as Frida, and Maria Izquierdo. I stayed in Mexico City for a while, also at the Anthropology museum where José Chávez Morado also painted; and from whom I received advice and friendship.

Q: Muralism was born out of the foment of the Mexican revolution and has often had a strong anti-imperialist and radical left political content, highlighting the contemporary struggles of Mexican workers and farmers, as well as the pre-colonial history of the country. Do you consider yourself an heir to this tradition?

A: From my youth while in school I always participated in groups that sympathized with the Mexican left. I won a state oratory contest on the subject of the Reformation Laws of Benito Juarez.

I identify totally with Muralism and its message in support of the downtrodden against Colonial Imperialism. I have inherited love of my Mexican roots and I admire the Chicano for their talent and resistance.

The spring [inspiration/mentor] which fed Diego Rivera was engraver Guadalupe Posada, who he met as a child when he went to study at the Academy of San Carlos in Mexico City,

The seeds of Muralism are epic, almost religious, and date from close to 10,000 years B.C. Stucco painting [from] the ruins of the Maya and Teotihuacan cultures are a very powerful antecedent in our Raza, a sign of our identity and love of our Mexican/American culture and a demonstration of resistance, defense of our values, our folklore, our food, mariachi music, our culture and our pole-flying dancers.

Chicanos are US citizens. They love the USA but carry in their heart indigenous roots and pre-Hispanic cultures, perhaps even more than Mexicans themselves who live in their own country. Muralism has been influenced by Diego Rivera and his expositions in the US and works displayed at the Museum of Anthropological history. The American culture has had a great impact. One example is that David Alfaro Siqueiros was Jackson Pollock’s teacher.

I took 70 works dedicated to Mexican plastic arts when Princeton University invited me. In 1993 and in 1994 Ms.Tipper-Gore offered me my first exhibition for Chicanos who worked so hard in the White House and in Congress, and I gave a conference in the Library of Congress on the works of Rivera and Frida Kahlo. I am grateful to have participated in this Chicano culture.

Q: Outside of the interview we talked a bit about your background. Before going to Princeton as an artist in residence you had always lived in Mexico, but your mother is actually Chicana. How did it feel to work in your mother’s homeland, and to make art honoring Chicano culture?

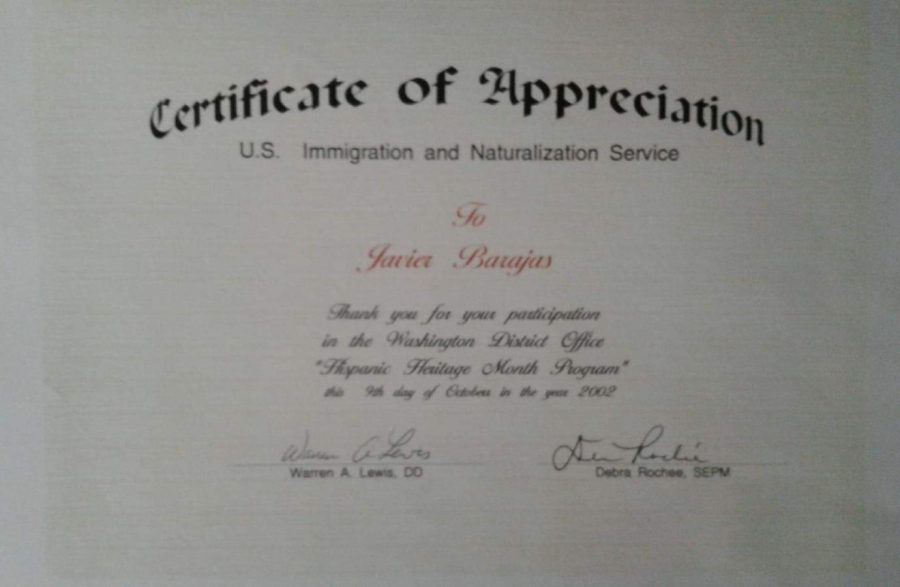

A: [In 2002 Bertha Corona of Princeton suggested Barajas to Library of Congress and INS officials in honor of Hispanic Heritage Month. The INS put on an exhibit of his paintings, and he was honored in a ceremony recognizing his achievements.]

For me it was like life had presented me [with] an act of revenge for the memory of my deceased mother. In her name, a Chicana, is how I have come to participate in the Chicano movement.

I have also been discriminated against in Mexico and have been persecuted and threatened, but I continue in my position of defender of the Mexican-American people’s art. The trade of being a productive painter is a bit lonely to allow concentration on work at my easel.

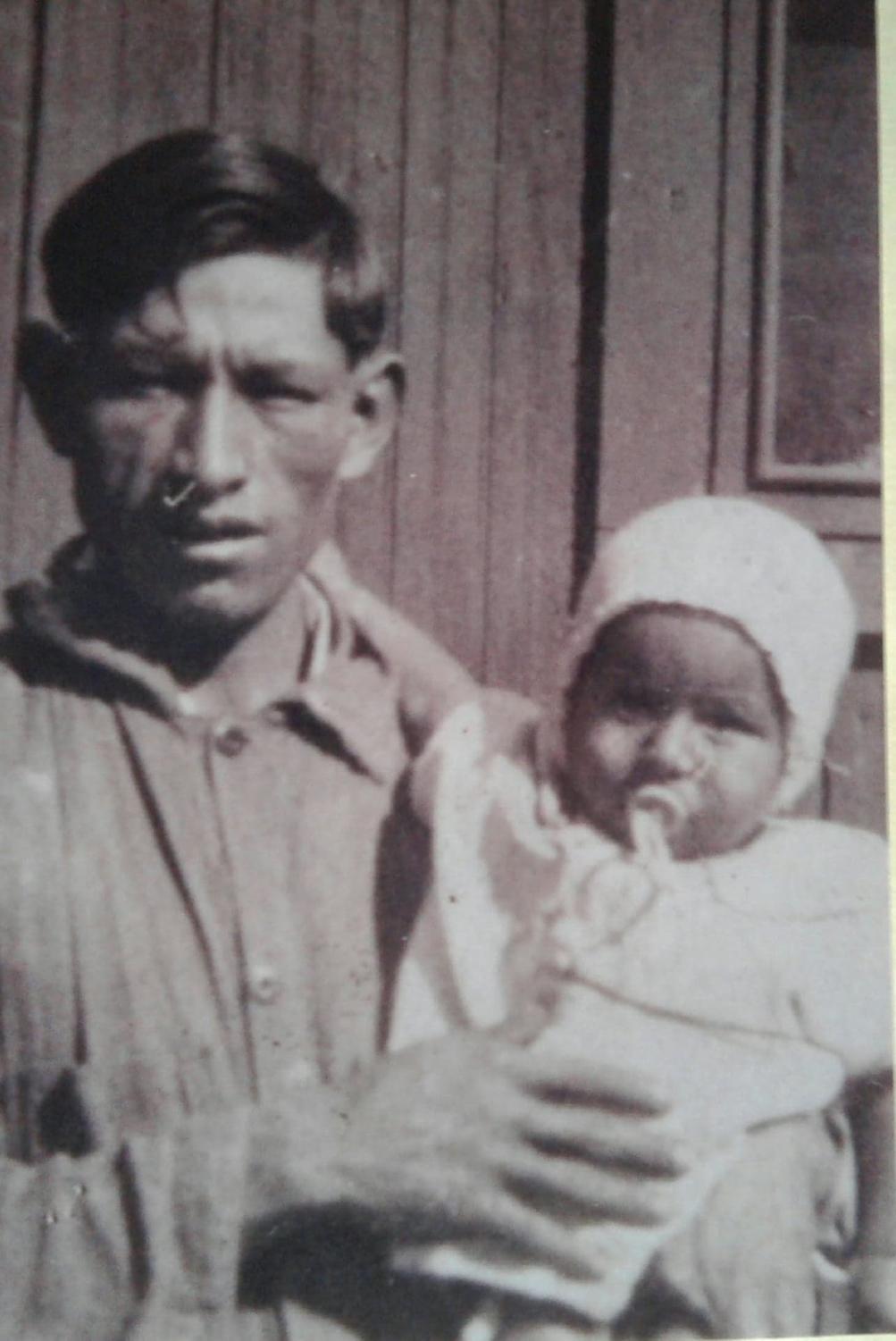

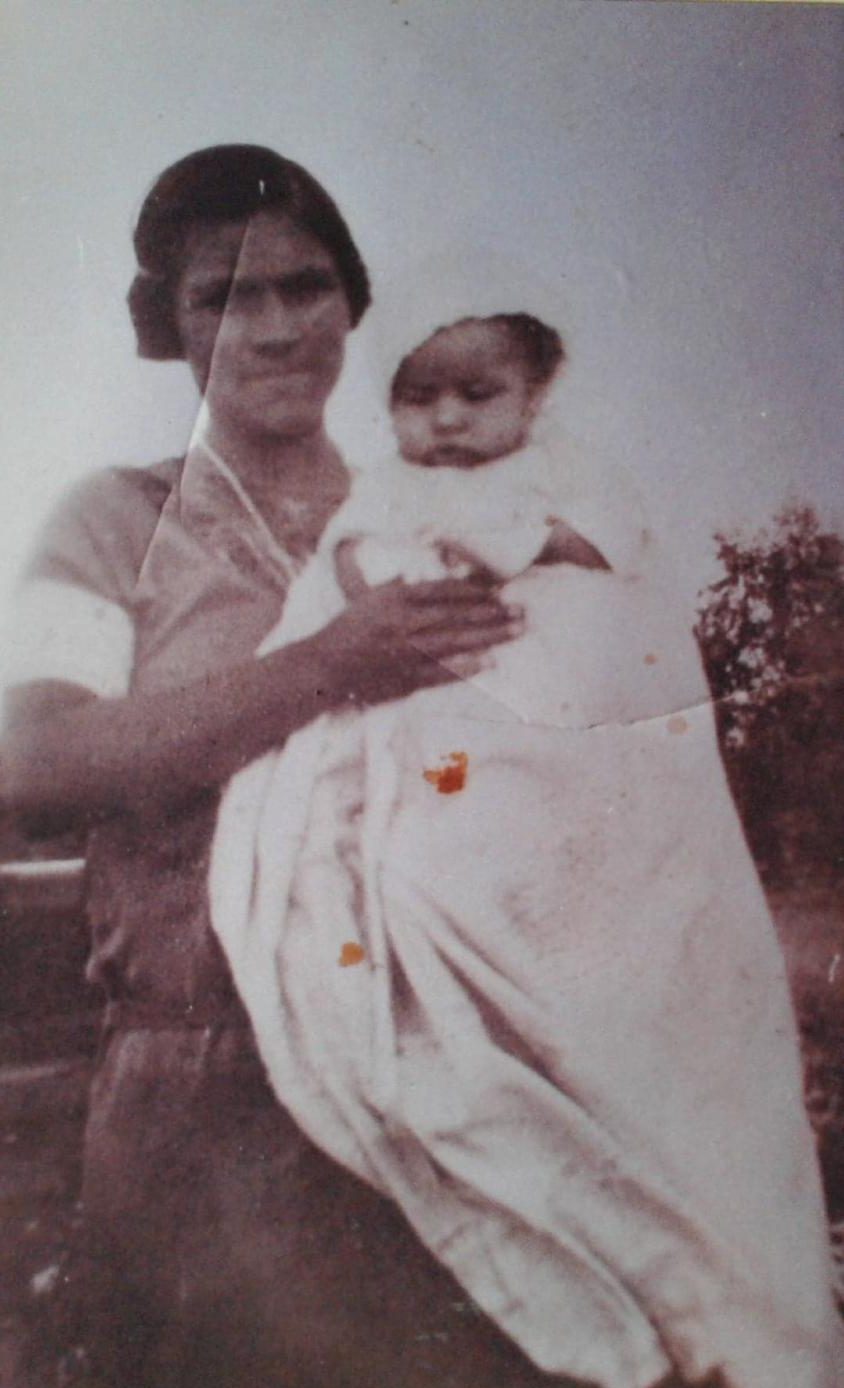

My mother’s history is very dramatic. She was deported in the ‘30s during the time of the Great Depression after being born in Richmond, California in 1927. Since she was a child she traveled in the arms of my grandfather, Socorro, on board a train carrying animals to the center of Mexico.

Close to 800,000 persons; adults and children, who were US citizens born in the United States. There is a movie which describes these events “My Family.” My grandmother carried the rest of her brothers and sisters, who were lost in the train ride. My mother was taken off the train with my grandfather in León. They never saw each other again. As an adult she returned to California in Richmond. In León she married my father who was a driver in my grandfather’s business. He was [a] second cousin to President Lázaro Cárdenas, whose government ordered nationalization of the petroleum industry. I followed my mother’s Chicano culture together with my aunts and cousins who resided in California.

Q: Guanajuato was the birthplace of the Mexican independence struggle, so I’m not surprised that it has its share of independent-minded artists. What was it like coming up as an artist in this community? Are there any of your peers whose work you would like to highlight?

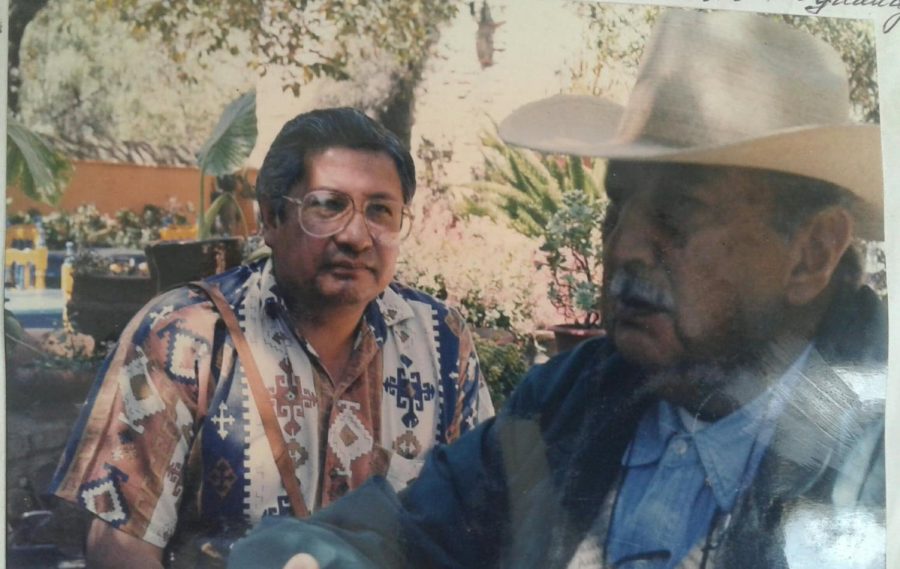

In Guanajuato for the past 35 years we have had a right-wing, conservative government [that] is opposed to muralists. Nevertheless, I received advice from my friend José Chávez Morado, from the past generation of Mexican muralists. His work is found in the Anthropology museum of The Alhóndiga de Granaditas – UNAM.

Q. You now live in Quintana Roo, on the Yucatán coast, famously a very beautiful area. Has the surrounding nature inspired any new ideas for your art? What is the artistic scene like in the area?

A: My stay at Playa del Carmen on the Mexican Caribbean allowed me to enjoy the beautiful turquoise blue colors and to analyze the Maya culture deeply embedded in the surrounding environment. Its exuberant vegetation was for me a place charged with energy. This fed and gave me the strength to continue painting. Now I am 70 years old and I feel grateful to still be physically and mentally well. With God, all my friends who have offered me their friendship and have acquired some of my works. In 2017 I was recognized in Slovenia, the first Mexican American to be entered in that beautiful collection. I donated a mural dedicated gratefully and with all due respect to Guadalupe Posada, for me, the founding father of Mexican plastic arts.

Q: CSU Chico has been labeled a “Hispanic Serving Institution,” meaning that more than a quarter of its full time students are “Hispanic.” Is there any message you would like to share with our Hispanic and Chicano students?

A: To the student body of Chico State: Thank you for preserving my painting dedicated to César Chávez and to our culture. I would say to them that I am proud to be part of their university, that my painting graces their walls. To be Chicano is a reason to feel pride for the essence of our anthropologic heritage, origin and identity. We are on our land, and it is in our blood.

Fight to be better. Honor the Chicano culture. It is very special and you are the vanguard of this generation, of youth enjoying spectacular advances by humankind, advances in technology. To be a student is a privilege and to be Chicano is a treasure.

Q. Would you be interested in doing more work for the University in the future if you were invited back?

A: Of course I would be very interested! Creating another mural requires an interesting theme. Dynamic support by the University and the Chicano movement count largely. I would seek to create a great work now with my span of 50 years [of] experience in the plastic arts.

Christopher Hill can be reached at Orionmanagingeditor@gmail.com. Answers have been edited for clarity. Sections appearing in brackets are summaries or paraphrases by the author.

A special thanks to P. Diane Schneider for assistance with translations.