As the threat of rain faded on a cloudy Monday afternoon, a brisk autumn breeze whisked us through the Chico Cemetery front gates as the tour commenced.

Around ten of us began our escapade through the cemetery at 3 p.m.

Chico State professor, Sarah Gagnebin, led the tour and imparted her knowledge about the history of the cemetery as well as the town.

The Chico Cemetery — on Mangrove Avenue — was built to be open and inviting to the public. The first burial took place in 1852, right around the time the Romantic Rural Cemetery Movement was taking the country by storm.

This 19th century movement sought to make cemeteries places of beauty and areas to reflect on death and life in the best way. Cemeteries during this time were designed to be garden-like and places families could go and have picnics. The Chico Cemetery is no different.

More elaborate architecture was one aspect of this movement. A Chico Cemetery example of this is the popular white Italian marble statue entitled the “Weeping Angel.”

Gagnebin said it is unknown who sculpted the “Weeping Angel” but it was commissioned by a member of the Simpson family in the early 1900s.

Not much is known about the Simpson family, Gagnebin said. They were well-off ranchers who moved to Chico from Orland, and after living here for a bit, moved elsewhere.

There are newspaper clippings from the 1900s that describe one member of the Simpson family, Leonora Louisa Simpson — who died in 1946 — shooting the local district attorney after being released from police custody, Gagnebin said. She was never arrested for shooting the DA; she was also known for vowing to never take a husband.

Gagnebin views the cemetery as a group of neighborhoods made up of different religions and roots, and the “Weeping Angel” is but one statue among them.

The tour began near the “Catholic neighborhood” which was easily the most colorful part of the cemetery. Gagnebin said while the grounds are maintained by the cemetery staff, the “Catholic neighborhood” is also cared for by a local Catholic church.

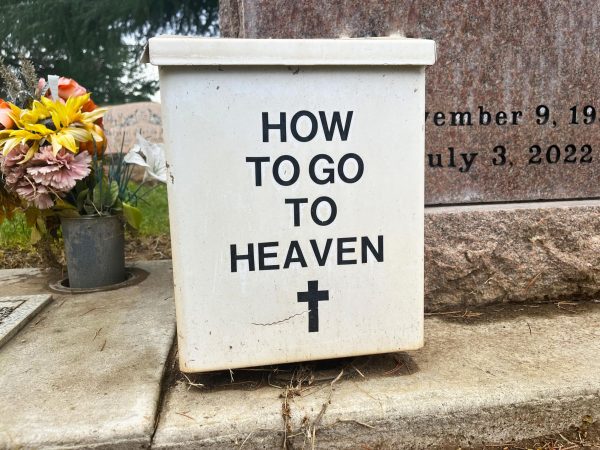

An interesting gravestone within this neighborhood includes instructions on how to get to heaven. The box shown above was empty when we went by, but Gagnebin said there are generally a couple Bibles inside.

Not too distant from the “Catholic neighborhood” is the “Chinese neighborhood.”

Now, there are only around nine to 12 gravestones in this neighborhood, but there used to be far more.

In 1892, a bone priest from San Francisco came to Chico and dug up around 135 bodies and took them back to San Francisco to perform the proper burial rites.

Most of those buried in the “Chinese neighborhood” were workers in the 18-and-1900s and the extensive burial rites were often not properly performed, causing anxiety to living family members, Gagnebin said. A lot of the headstones in this neighborhood didn’t even have names and only had “Chinaman” engraved upon them.

From here, we burrowed deeper into the depths of the around 58-acre cemetery, where we found the “Kyte” headstone, one of the few zinc headstones in the Chico Cemetery.

Zinc headstones became popular around the 1870s and were marketed as being more ecologically-sound and cheaper than stone counterparts. These headstones were also hollow.

Gagnebin said there are no specific records of this happening in Chico, but these hollow zinc headstones — like the “Kyte” headstone — are thought to have been used to hide alcohol during the prohibition.

Once past this possibly scandalous hiding spot, we transitioned into the “historic neighborhood.” Where the grave of Chico founders John and Annie Bidwell can be found.

After John Bidwell’s death in 1900, his wife, Annie, originally did not want a headstone for her husband, but eventually commissioned a small boulder from the surrounding area to be carved and set at John’s grave.

After she died in 1918, their gravestone became a popular historic monument, but cemetery visitors had a hard time finding the small headstone. The Chico Cemetery then raised enough money to get a bigger boulder with a plaque for the couple’s headstone.

They are buried on what’s called “founder’s row.”

Past the “historic neighborhood” is one of the “military neighborhoods.”

There are multiple military sections and monuments, one being near the cemetery’s front gates. This monument pays homage to the 52 U.S. submarines and crews that went down during World War II.

The torpedo was donated by an Orland woman in the 1990s, according to Gagnebin.

Between the “historic neighborhood” and “pioneer neighborhood” is what’s considered the “segregated section.”

It is thought that when the cemetery expanded some of the graves in the segregated section were “almost certainly” paved over to make paths, according to Gagnebin. It is unknown how many graves could be under the pathways.

Past the “segregated section” is the oldest part of the cemetery, the “pioneer neighborhood.”

The very first recorded burial was in 1852. Amos Frye was buried by John Bidwell after Fry died leading a raid against the Mill Creek tribe. He accused them of stealing his cattle. It’s unknown if this claim was true, Gagnebin said.

The “pioneer neighborhood” is also home to some of the oldest trees, which poses a safety risk. Gagnebin told the group that if we heard a crack, to run. A lot of gravestones in this area are cracked or broken due to fallen branches. The ground in this section is also sunken.

Now, California state laws require a certain amount of dirt, cement, metal and such — depending on the type of burial — to be over the casket or vault to prevent the ground from caving in. However, these laws did not exist when Chico was founded.

There are over 34,000 graves in the Chico Cemetery, some of which are unmarked. The three oldest, readable gravestones belong to the Laurence siblings.

James Laurence died at the age of 15 in 1853. His sister Mary Laurence died a little over a month later at 20-years-old. Then their sister, Sarah Ann Laurence, died at 18-years-old another month later.

Gagnebin said it is unknown what they died from, but sickness is one of the many possibilities.

One of the last prominent sections in the cemetery is the “Freemason neighborhood.”

The Freemasons are a fraternity that can trace their origins back to early stonemason guilds. It is one of the oldest fraternities and only allows men into its ranks. The only women allowed to be buried in the Freemason sections are the wives of members.

There are other Freemason members buried in other parts of the cemetery.

John Bidwell was briefly part of the Chico-Leland Stanford Masonic Lodge No. 111 ranks at its inception.

The Chico Cemetery is a history of the town and its “death ways,” according to Gagenbin, and it “tells us about our history and how our death ways will always change.”

Who would’ve known so much town history is hidden next to a main thoroughfare?

Gagnebin often reminded us Chico Cemetery is, overall, a business. The cemetery still sells plots and is even expanding by introducing its new Garden of Trinity, shown above.

The Chico Cemetery Association hosts its own monthly tours. To find out when the next tour is and book your spot, call them at 530-214-0088.

Ariana Powell can be reached at orionmanagingeditor@gmail.com or alpowell1@csuchico.edu.