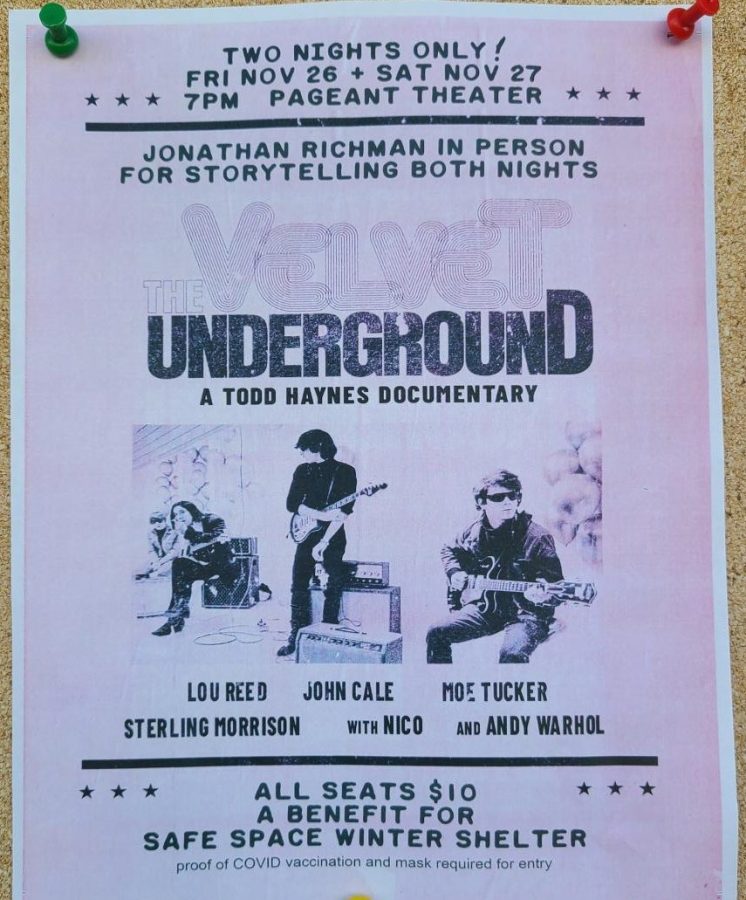

Pageant Theatre returns with guest Jonathan Richman for Q&A

The Pageant Theatre on the corner of Sixth and Flume Street

The Pageant Theatre lit up their projection screen to astound attendees for the first time since the pandemic.

The Modern Lovers’ founder Jonathan Richman showcased at the theatre from Nov. 26-27 to share stories and music lessons about The Velvet Underground.

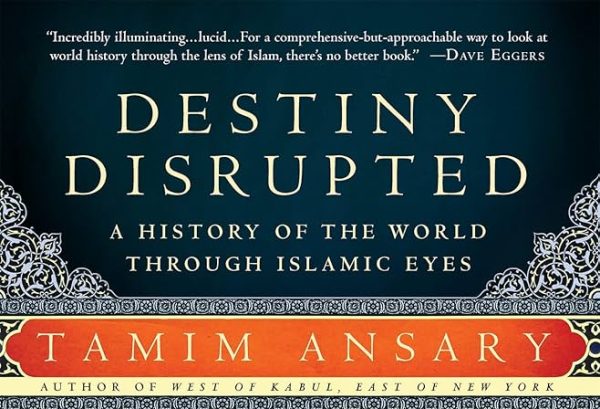

The theatre held a special viewing of Todd Haynes’s new documentary, “The Velvet Underground,” about the band’s story and significance to music’s history. The film was followed by a Q&A with Richman, who started as a fan and became the band’s musical apprentice.

When Richman was 16 years old, he was invited into a club where he saw the band play for the first time. He said the band recognized that his love for them came from his fascination with music theory. Consequently, they taught him about music. Soon, with The Modern Lovers, he would open for their shows.

After the film, Richman told the audience that he still remains a little uncertain about why he was in the documentary. However, he attributed his appearance in the film to being their fan-turned apprentice.

“I was a little squirt who had to be in the movie,” Richman said.

Since his first introduction to the band, Richman has attended around 60-70 of their shows. The apprenticeship led to Richman starting The Modern Lovers in 1970 with the help of producer John Cale, co-founder of The Velvet Underground.

My introduction to Richman’s music was his performance of “That Summer Feeling” in the corner-store scene of the Farrelly brothers’ 1996 comedy “Kingpin,” starring Woody Harrelson.

Richman attributes his influence in music to surrealist painter Salvador Dalí, whose famous works include “The Persistence of Memory” (1931).

“I was looking for that dreamscape,” Richman said.

In the same whimsical nature as his solo songs like “I Was Dancing In The Lesbian Bar” and “You’re Crazy For Taking The Bus,” Richman turned his storytelling into a lesson on The Velvet Underground’s use of music theory.

Until the 20th century, many audiences didn’t like the out-of-tune sound of equal temperament. The Velvet Underground, whose members were Lou Reed, John Cale, Maureen Tucker, Sterling Morrison and Nico, arguably revolutionized this perception of harmony.

Richman played a major third on a piano in the screen room to teach us about equal temperament. This tuning system was a 20th-century phenomenon that replaced earlier “just intonation,” a scale from the overtone series — the basis for jazz. It enabled keyboardists and pianists to compromise, playing equally well in any key.

In the film, Richman credited The Velvet Underground’s “group sound” to their harmonic layers. The film dove deeply into the band’s trademark time-bending sounds and D-tuned guitars.

Richman especially credited Tucker, who played a snare drum and kick drum turned on its side with mallets.

“Her beat would inspire everything the band did,” he said to guests.

Covering the band’s anti-hippy look and musical involvement with the underground gay community, the film takes us back to 1960s New York City, when film shifted from narrative storytelling to other art forms.

Richman, who is also an artist, met pop-artist and filmmaker Andy Warhol, who invested in the early success of The Velvet Underground.

A crucial element to The Velvet Underground’s rise to fame, Warhol’s Factory played a huge role in the documentary. It’s credited with originating the contemporary image of fame. Artists, models and creative-minded people from all around came to the Factory and wanted to work with Warhol just to be seen, when this new idea of glamor was emerging in pop culture.

Interested in film and art, Richman tried to form a working relationship with Warhol like he did with The Velvet Underground. Unfortunately, the shooting of Warhol interrupted that chance.

“Once he got shot, all bets were off,” Richman said.

The documentary said The Velvet Underground did with music what avant-garde artists did with film and literature.

In the film, artist and composer La Monte Young described the electric hums of the band’s natural harmonics as the “drone of Western civilization.”

Although their style and attitudes did not align with the usual themes of the hippy subculture, The Velvet Underground’s dreamlike sound created an audial portal that was as kaleidoscopic as the love-and-peace anthems of the complementary “flower child.”

Their music represented grace within the struggle to go through the fixed constraints of society to reach light and liberation. You can hear that diamond in the rough being extracted through the harmony found in the seemingly dissonant chords of their music — the same way Richman found his joy as an artist through the uncertainty of his youth that took him there.

Shae Pastrana can be reached at orionmanagingeditor@gmail.com and @Pineyfolk on Twitter.