Bird flu lands in Butte County

A Northern Shoveler on display at Chico State’s Vertebrate Museum (Holt 237). This species has the highest rate of naturally occurring avian flu of any local species. Photo taken by Noah Herbst, Aug. 26, 2022.

Butte County Public Health (BCPH) has declared a local health emergency after Avian flu, a disease that stems from the type A influenza virus, was detected in the county.

According to a press release from BCPH’s Facebook account, the organization declared an emergency on Aug. 17, after learning from “the Butte County Agricultural Commissioner’s Office (BCAG) that avian influenza has been confirmed in a domestic flock of birds located in Butte County.”

After years of COVID-19, and amid growing concerns over monkeypox, the last thing most people want to worry about is another contagious virus.

The type A influenza virus is related to the same influenza virus that causes the seasonal flu. The viral infection, which is found naturally in some wild birds, such as ducks and geese, spreads between birds and can be transmitted from birds to humans.

The current virus, also known as H5N1, is descended from viruses that first emerged in China in 1996-1997, which is where the first human cases were reported. Although, avian influenza has long been found in the stomachs of wild birds and did not originate there.

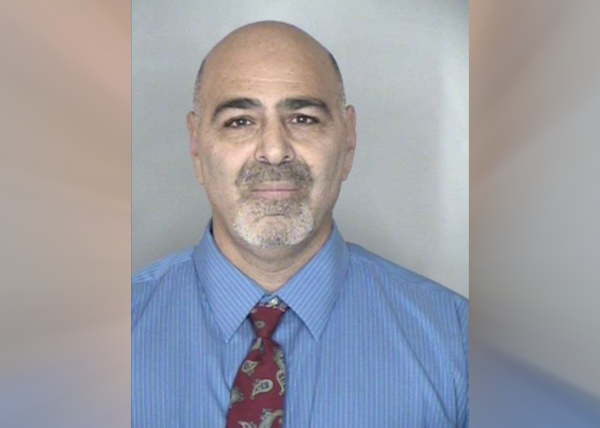

Dr. Troy Cline, an associate professor at Chico State whose research specializes in avian flu influenza, doesn’t believe the general public should be too concerned.

“We’re not looking at like an impending COVID situation where a few people are going to get infected and spread it all around the state, country or world,” Cline said. “There are changes that would have to occur to the virus to allow for that to happen.”

Though it’s always possible that the virus could mutate, the scientific community has not yet seen any compelling evidence. Fortunately, this means that cases of humans contracting the disease are fairly uncommon.

“[It’s] different from the human influenza viruses in some important ways that make it rare or difficult for an avian influenza virus to infect a human, and vice versa, for a human influenza virus to infect a bird,” Cline said.

Another reason human cases are rare is due to how the virus spreads. A person would have to come into direct contact with an infected bird, and be exposed to their saliva, mucus, excrement or other bodily fluid to become infected. Human-to-human transmission is extremely rare, with very few cases ever recorded.

For the average person, the risk remains low. However, for those working jobs where close contact with birds is a regular occurrence, like in the commercial poultry industry or in state and federal wildlife areas, contracting the pathogen is more likely.

Once a person is infected — the consequences can be dire. The virus affects the respiratory system and can result in a manifold of symptoms. These include:

- Coughing

- Shortness of breath

- Headaches

- Fevers

- Sore throat

- Muscle aches

- Nausea and vomiting

- Diarrhea

The outcome can be deadly. Dr. Cline said that close to half of all recorded cases result in death.

“If you get a symptomatic case of influenza, the mortality rate is really high,” he said.

The only reported case of an American contracting the disease was in April, when a Colorado man became infected. He experienced only minor symptoms and has since recovered.

Since it was first detected in the late 1990s, fewer than 900 cases of avian flu in humans have been reported globally, though it’s worth noting that asymptomatic cases may go unreported.

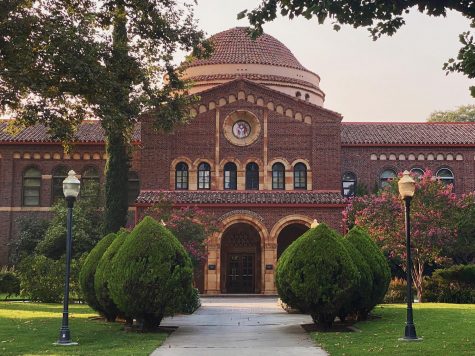

For several years Dr. Cline has been running and operating a lab on campus where students can study avian influenza in the local bird populations.

“We collect samples from hunter-killed waterfowl, bring the samples back to the lab and we process the samples and test them for the presence of the avian influenza virus,” Cline said.

This process occurs between the months of October and January, where the researchers wait eagerly for the chance to collect a sample during these chilly, winter mornings.

They have found that of the local waterfowl in the area, the northern shoveler has the highest rate of avian flu prevalence at 20%. This is about twice as much as the other local migratory waterfowl in the region.

Cody Frazer, a former pupil and current lecturer in the Biological Science Department centered his graduate thesis around the northern shoveler. He explored why the species had higher rates of avian flu. Focusing on the northern shoveler’s gut microbiome, where bacteria and the virus live, Frazer found that the birds had a stunning lack of diversity amongst their microbiomes.

His thesis revolved around defending his position on how less diversity in the gut microbiome is related to a higher prevalence to the virus.

Another graduate student in the program, Caylin Stanley, conducts research on the opposite end of the spectrum. She studies wood ducks, a migratory aquatic bird that lives in the area during the summer, when most other birds migrate north. What’s fascinating about the wood duck is the fact that during the winter, most waterfowl in the area have an avian flu prevalence rate of around 10%, whereas wood ducks exhibit a 1% prevalence rate.

“While my research is focusing on why they [northern shovelers] have this huge amount of bird flu, she’s trying to figure out why wood ducks have almost none. If you’re asking my opinion, I think her research is way more interesting,” Frazer said with a laugh. “It’s a lot more fun to know what’s stopping this virus than making it worse.”

For waterfowl, the pathogen’s natural carriers, the virus is often not lethal and symptoms are extremely rare. However, for domesticated birds the mortality rates are much more severe and can even reach 100%. The current strain of the virus has been moving throughout the U.S. for the past several months, affecting over 40 million birds since early 2022.

“We are definitely in the midst of another bird flu outbreak,” Frazer said.

The epidemic has affected 39 states, and California has seen four counties report cases in August alone — Sacramento, Butte, Fresno and Contra Costa. Butte, Contra Costa and Sacramento counties had relatively minor outbreaks in “backyard flocks.” But, in Fresno County the situation reached new heights when a commercial poultry producer was forced to euthanize nearly 34,000 chickens in an effort to mitigate the virus.

“That’s kind of the big issue around here,” Stanley said. “We have a lot of domestic poultry and we have a lot of waterfowl, so the mixing is kind of the concern.”

Luckily, because avian flu is a global phenomenon that flares up on occasion, government agencies are well-equipped to deal with it.

“The protocols that were put into place when the virus was detected in Butte County are protocols that don’t have to be employed frequently here or in the United states, but are employed more frequently in other parts of the world,” Cline said. “So agencies were ready to go when the virus was detected here, and to take care of that situation quickly to try and limit its spread.”

If you or someone you know owns domestic birds, or regularly comes into contact with wild or domestic birds, keep an eye out for these symptoms:

- Stumbling or falling

- Sneezing

- Coughing or difficulty breathing

- Hens with a drop in egg production

For questions about avian flu or to report a sick bird, call the avian flu hotline at 866-922-2473.

Noah Herbst can be reached at orionmanagingeditor.com or @NoahHerbst13 on Twitter.