Students, community advocate for sanctuary city

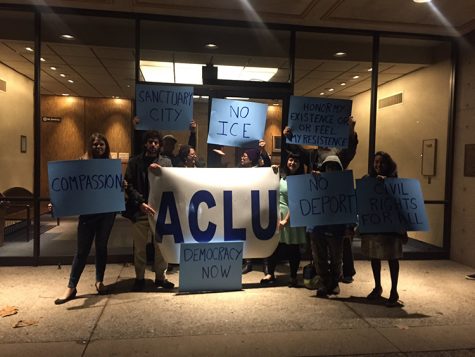

Students gather before the city council meeting to discuss their action plan. Photo credit: Bianca Quilantan

Karla Guzman came to the United States 14 years ago when she was 6 years old. As an undocumented student, she recalls being fearful of deportation when police officers came to her home after someone tried to break into her childhood room window.

“Even though what had happened wasn’t our fault, I couldn’t shake the thought of the possibility that they would take us away or even worse,” she said. “The thought went so much into my head that I took down a Mexican flag that hung in my room so they wouldn’t question if I was from here or not.”

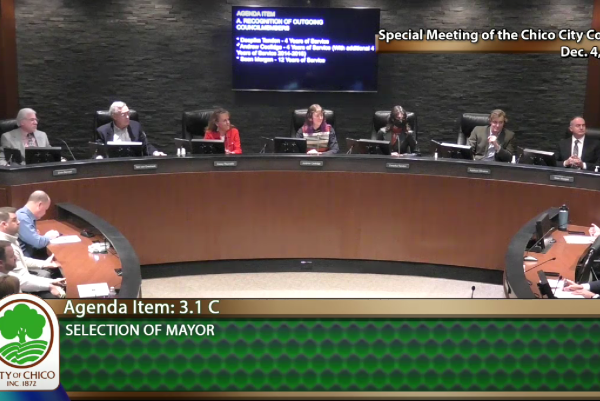

Guzman, an undocumented student, was one of 37 students and community members who signed up to speak to the Chico City Council about why they should discuss the possibility of becoming a sanctuary city. The Council voted no in a 4-3 vote.

Asa Mittman, chair of the Art and Art History Department, started the sanctuary city movement in early December as a response to the presidential election results. He reached out to groups on campus, community supporters and city council members.

“The only antidote for all of the anxiety and fury that a lot of us are feeling is action,” Mittman said. “So I contacted all the members of the city council and said we have to do something about this and only a single one of them responded, Ann Schwab.”

Sanctuary city is a term that has been used in light of the recent political climate for cities that welcome undocumented immigrants and refugees. Butte County already has some “sanctuary county” measures due to the TRUST Act of 2014. California state legislators are also discussing becoming a sanctuary state.

“The thing about the term sanctuary is it doesn’t actually have a fixed legal meaning, there is no official status,” Mittman said. “What it generally means is kind of a statement that a community, city, state has decided that its law enforcement should not collaborate with federal immigration authorities.”

Before the vote, students shared testimonies of why the council should consider discussing becoming a sanctuary city. Many also shared their undocumented status.

William Mendoza, a third-year political science major and president of La Raza Unida, said the council should consider the discussion because recent rumors of ICE in Chico have made students uncertain about their academic futures.

“I am an undocumented student,” Mendoza said. “I have a 3.6 overall GPA at Chico State and I believe that my education should not be at risk because of my legal status. It is unjust for a person like me, who is pursuing a higher education, to have that fear in their life. Knowing that the next day is not promised and knowing that everything that they’re working for right now can be thrown away.”

Elizabeth Alaniz, assistant director of the Financial Aid and Scholarship office and LEAD adviser, has lived in Chico for 28 years and remembers when ICE came to the area.

“One of my early memories is having ICE come into my house with shepherd dogs and I don’t want that to happen to again here,” she said. “Regardless of what you think about immigration, these students are here.”

Chico residents ask #CityCouncil to be a sanctuary city @theorion_news https://t.co/0VYs4SLC3N

— Bianca Quilantan (@biancaquilan) February 22, 2017

Guzman said she believes not all law enforcement is bad because they are a sign of protection.

“I can’t help in my heart feel fear if I can’t count on them to stand down from any deportation orders to protect me and the hundreds of other undocumented students,” Guzman said. “When the incident in Oroville broke out, Chico was quick to respond to protection in sheltering those who were evacuated. Why not do the same with your own community members that love Chico as much as you do?”

Cassandra Hernandez, a third-year criminal justice and multicultural studies major, said a sanctuary city discussion is necessary to ease students’ fears of deportation.

“Something that a lot of people of color can’t do is explain to their families “I’m going through debt, I’m going through hunger, I’m going through a mental illness’ and now something that a lot of us can’t speak to our parents about is ‘mom I can’t go outside because of ICE. Mom, I can’t do this because I am afraid.’

“Now not only do I have to worry about my school, my work and how my family is doing, now I have to worry if I’m going to see my friend the next day—if he has been deported, if he has been taken. We aren’t numbers, we are actual people.”

After the vote, emotional outcries and boos from numerous supporters echoed in the Chico Council Chambers.

Daniel Lopez, an undocumented student and first-year social work major, said the community support was moving but the vote was disheartening.

“Hearing the rest of the people talk, I broke down in tears because there was so much support,” Lopez said. “My tears of happiness were quickly turned into tears of distress, sadness because even with all of that support, our city council said no. It’s heartbreaking to see them not care about the people they represent.”

Edir Gutierrrez Salgado, president of LEAD, said all they wanted from the council was to have a future discussion.

“I was hoping they would have a conversation,” he said. “For them to consider it, to really look inside their hearts and say what is it that we can do, not just to dismiss it the way they did.”

After the meeting, a debriefing was held at the Cross Cultural Leadership Center to allow students and allies to discuss their thoughts about the outcome of the council meeting.

Strategies for the next steps were discussed, including one that proposed boycotting Mayor Sean Morgan’s classes. Krystle Tonga, CCLC assistant program manager, said she believes the idea was suggested out of emotion and was quickly shut down.

“There was a pretty wide consensus that as a professor he has the ability to be free to express his opinions,” Tonga said. “Where we need to draw the line is, just as we are able to be free in our speech, we also need to allow those who don’t agree with us to be free in their speech. If we hinder their speech, we hinder our own speech.”

Strategies include:

1. Talk to the Chico Police Department.

2. Set up a community response team.

3. Keep pressure on the city council and continue to attend meetings.

4. Weave in the sanctuary city idea during public comment.

5. Fill out a Google Doc with statistics and facts to share at city council meetings.

Bianca Quilantan can be reached at [email protected] or @biancaquilan on Twitter.