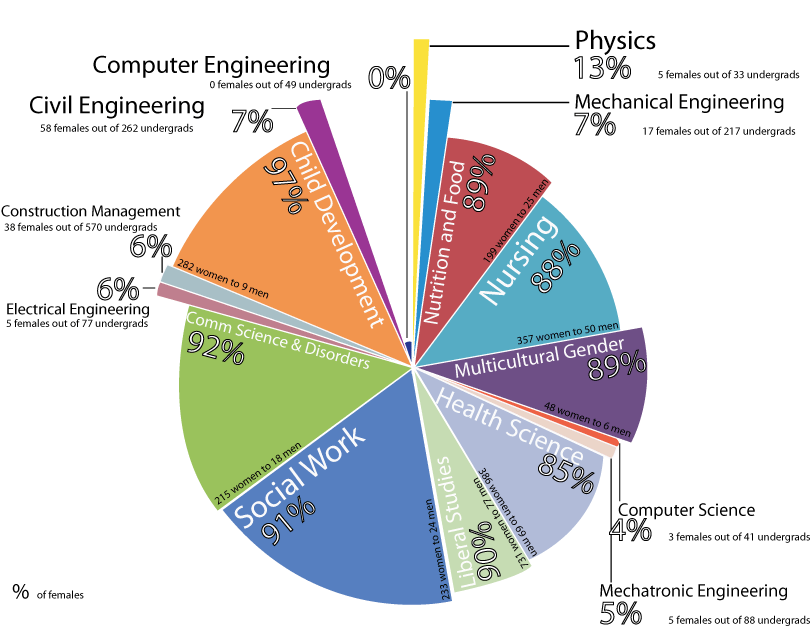

Women at Chico State are widely underrepresented in the science, technology, engineering and mathematics fields.

Few female students have graduated with degrees in computer science, computer engineering and electrical engineering in the past four years, according to a study by Jeffrey Bell, chair of the biological sciences department.

The study covers 2010-2014, showing that four percent of graduates in computer science and six percent in electrical engineering were women.

No female students graduated with a computer engineering degree.

Michelle Rodriguez is the only woman double majoring in computer and electrical engineering at Chico State.

“If a lab is due and I didn’t get it, I not only feel like I failed myself, but every woman behind me,” Rodriguez said.

Chico State is not an anomaly. Women earn about 60 percent of bachelor’s degrees overall nationwide, according to an article by the New York Times.

However, only 20 percent of degrees in computer science were earned by women and 18 percent of degrees in engineering.

Melody Stapleton, chair of the computer science department, said when she came to Chico she was the only woman with a doctorate in a department of more than 20 people.

“I was kind of a pioneer,” Stapleton said. “There were no tenure-track women in the entire College of Engineering back then.”

Being smart and pursuing an education in science or math may not be seen as trendy for women, she said.

“America’s culture is so pop-oriented and what’s portrayed to the youth as being hip is not women in science,” Stapleton said.

Starting a family is also a priority for many women, said Colleen Bronner, a civil engineering professor.

When Bronner was in college, a female engineering lecturer visited her school and said that women in the field need to focus only on either their careers or having children, not both, Bronner said.

“There are women out there who are more than willing to help, but there are also women who think they have found the right path and believe everyone needs to follow that path, and in my opinion, that’s silly,” she said.

Suffering through blatant and subtle sexism is also a risk for women seeking math and science degrees, Bronner said.

“There are some old school men who aren’t huge fans of women in engineering or having a woman as a boss,” she said.

When Bronner studied in Japan, she dropped a class because the male professor was sexually harassing her and the other female students in the course, Bronner said.

Rodriguez remembers walking into her first science lab as a first-year and a male student told her she was in the wrong class.

“I looked at him and said, ‘No, I belong here too,'” she said.

Often, if a woman succeeds in these fields, her academic accomplishments are ignored and her success is attributed solely to her gender, Bronner said.

“You get told that if you’re getting an A, you’re getting that grade because of inappropriate relations with the professor or because they need to keep a quota of females,” she said.

A study done by the U.S. Census Bureau in 2011 revealed that a quarter of workers in science, technology, engineering and math fields were women.

This kind of disparity may deter women from pursuing degrees that would lead to those professions, Bronner said.

Erin Baumgartner, a third-year electrical engineering major, said that by the time she gets to the job market, she will be used to being a minority.

“It’s just going to push me to try harder,” she said.

Madison Holmes can be reached at [email protected] @madisonholmes95