Although March is only beginning, students around Chico State are already sporting shorts and sunglasses with the prospect of continued warm weather, thanks to El Nino.

The hype behind El Nino seems to stem from a lack of understanding of what this weather phenomenon actually is and how it can affect California, along with other parts of the world.

“What I hear from a lot of my students is that they think El Nino is synonymous with extra rain, but in fact, it’s a whole variable, and El Nino and La Nina years are based on temperatures in the oceans and sea surface temperatures along with wind speeds and pressures,” said Eric Willard, a professor in the geological and environmental sciences department.

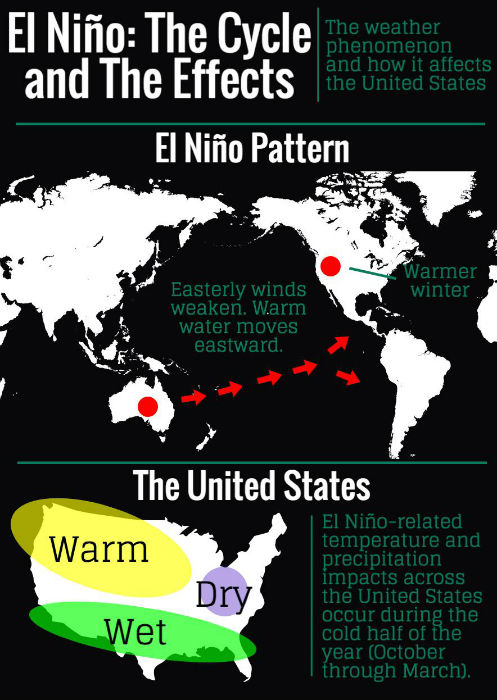

Basically, global climate is complicated and can be difficult to predict since weather trends, especially in California, can be irregular. The key change that occurs with El Nino is the unusually warm ocean temperatures in the Pacific Ocean mainly along the equator, or the “warm phase” of a larger phenomenon called El Nino-Southern Oscillation. It’s counterpart, La Nina, is the “cool phase,” and all together it impacts weather and climate around the world.

El Nino develops most over North America during winter seasons, which includes warmer-than-average temperatures in the western and northern United States along with western and central Canada due to winds blowing in an unusual reverse west-to-east direction. This allows warmer water to spread all the way down to South America instead of the typical winds pushing it toward Indonesia and Australia.

There is talk about the big impacts that are expected this year, which based on the 1997-1998 El Nino is worrisome, especially since there’s no way of predicting whether the outcome will be worse.

“If you want to understand El Nino, the difficulty is that every El Nino event behaves differently. Since it’s not always the same, it’s very difficult to predict and it’s very complicated,” said Jochen Nuester, geological and environmental science professor.

One thing is certain though: El Nino has the potential to bring a lot of water back to California. Such year-to-year variation between wet and dry years is a California characteristic based on drought history.

“These droughts are nothing new to California; it’s cyclical in nature, and the last big drought, like the one that we’re seeing currently, happened in 1977,” Willard said, “so if you look back historically at trends and rainfall and precipitation, we’re mirroring that drought closely in terms of overall rainfall.”

California’s relationship with water has much to do with the natural landscape of the state. The Pacific Ocean is the primary basis for California weather, not just during El Nino phases. The Mediterranean-like climate, with wet winters and summer droughts, is a natural occurrence for west coasts of continents in middle latitudes because of atmospheric pressures over oceans.

California is also a large state with heavy rainfall in the north and not so much in the south, so water must travel the 800-mile stretch down to Southern California without evaporating back into the atmosphere, being used by plants or soaking deep into groundwater basins.

The fluctuation of water supply coming from Northern California mountains can be seen in Big Chico Creek, based on when the stream was nearly empty in fall 2015 to the heavier flow that followed the rainy season in December and January. Though it may appear that the Creek is losing water lately, it is in fact due to water protocols and distributions.

“There are diversions just to the northeast of Chico if you go up to Upper Bidwell Park, so if we have a certain amount of flow, a certain amount of rainfall in the mountains or the foothills and we’re expecting flooding, then they divert the excess water right around Chico and send it through Lindo Channel or Mud Creek,” Willard said. “The fluctuation in the stream flow is related to how much rain we get here in Chico, but also how much they receive up in the foothills and all the tributaries and the streams that come and feed Big Chico Creek.”

While much of the perceived water shortages are actually based on Pacific Ocean winds and distribution systems throughout California, there are still significant impacts made by individual daily choices with water, and the demand far exceeds the supply.

Drought awareness has been emphasized on Chico State’s campus, but with the hope that El Nino brings, along with the 40 million people throughout the state that still see water as instantaneous gratification, California citizens still waste water.

“Most likely we’ll get a lot of rain like a lot of people were hoping would happen this year, and our reservoirs will fill back up, and everybody will go back to life as usual and not be concerned about the rainfall. Then in another 15 or 20 years we’ll have this whole process take place again where people panic about water, so it’s nothing new,” Willard said. “People expect to be able to have lawns and showers and expect to be able to turn the faucet on and have drinkable water.”

Christine Zuniga can be reached at [email protected] or @kissssteen on Twitter.