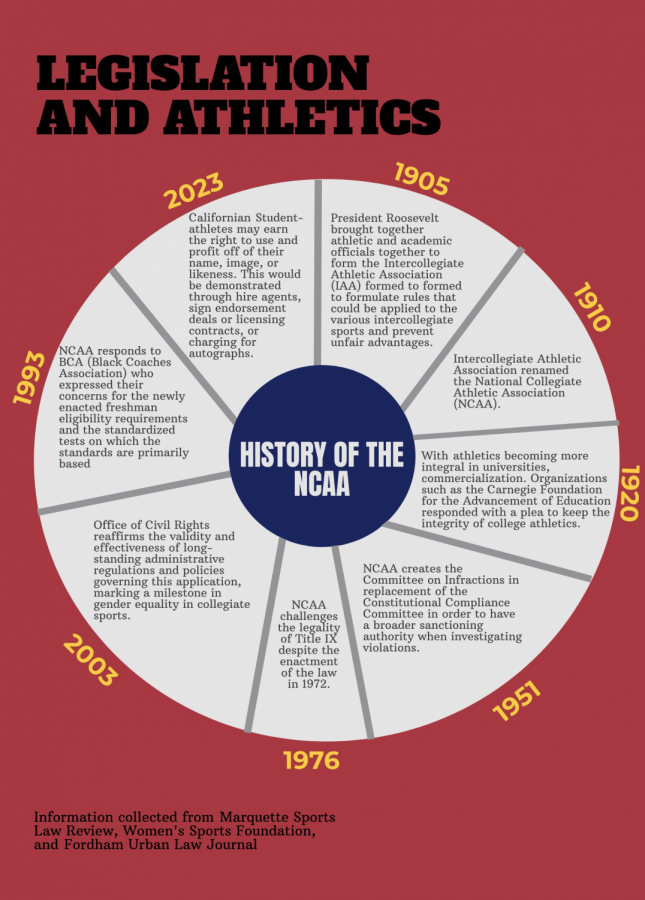

For years, student-athletes have fought for the right to earn benefits in return for the work they put into playing in order to place their school on the map. On Sept. 30, California changed the game forever as it became the first state to bring this issue into the spotlight, as Governor Gavin Newsom signed the California Senate Bill 206–or more popularly known as the “Fair Pay to Play Act.”

Contrary to popular belief, the signed bill will not result in college athletes receiving a salary from their school, but rather the rights to use and profit off of their name, image, or likeness. This would be demonstrated through hire agents, sign endorsement deals or licensing contracts, or even charging for autographs.

However, in the case that this bill does not get struck down, it will only begin to go into effect starting 2023.

While many student-athletes believe that this legislation is long overdue, schools, lawmakers and athletic associations such as the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) have been quick to make their case opposing the bill for the same reasons why it took so long to be signed in the first place–this update could revolutionize collegiate athletics for better or for worse.

Those opposed to the bill still have athletes at heart but want to make sure students are more focused on earning their studies, not their salaries. Others fear that the integration of agents would result in certain schools having an advantage in recruiting, thus spoiling the historic appeal of collegiate sports where students are acknowledged for their raw talent, not their networks.

For supporters of bill 206, the ratification of the law would reinvent sports to the benefit of the athletes who are held to the standards of professionals but not treated as such. Responsibly compensating athletes would not only be fair but level the playing field.

Many students who sign with schools are sold on the idea of receiving an initial athletic scholarship and the temporary benefits, but find themselves struggling to afford food and housing. Few players become professionals, while the rest who still dedicated themselves to their sport, leave with an incomplete degree, and no money from their collegiate career.

Although the bill cannot be integrated until 2023, many students have already formed their opinion on the subject–especially those who may reach the 2023 bill before they graduate.

“[The bill is] Definitely long overdue, it’s not something you would think of right off the bat, but it also should be acknowledged.” Cielysse Robinson, a freshman and outside hitter for Chico State’s volleyball team said.

“Student-athletes put a lot of work into the school, we do more than just be in the classroom, go home, and do our daily lives. We go to class and then straight to practice right after, it’s a hard 12-hour day. We’re tired, and have to wake up every day and do it again,” Robinson continues.

“Student-athletes work hard regardless, but people, in general, would do anything for money, it’s fair. But being able to earn a profit off of this would just be a plus.” ends Robinson.

Aside from the morality and rationality of compensating students, another issue is at play with the NCAA, which is integrated with schools across the country–including the California State University system to ensure student athletics are fair and safe. The bill signed by Newsom directly violates the rules set by the NCAA and if not amended, could result in ineligibility for Californian schools to participate in their highest-turnout conferences.

For now, students will have to wait until the ball is in their court.

Kimberly Morales can be reached at [email protected] or @kimberlymnews on Twitter.