The corners with the white crosses: Why roadside memorials matter

The meaning and value behind public memorials of tragic loss.

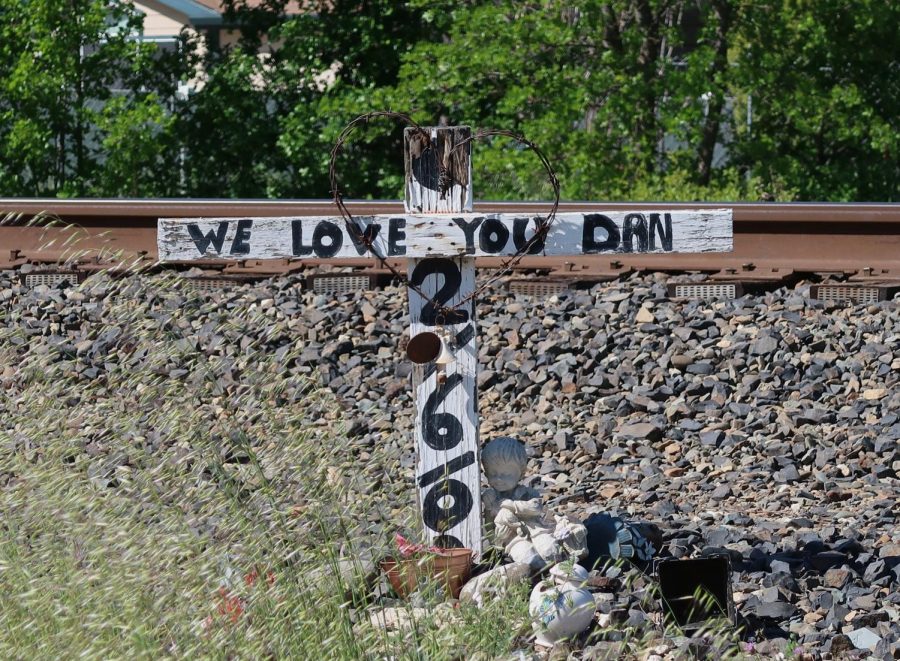

The details of his death are hard to find, but this memorial for “Dan” is well-maintained, with a hidden path through the grass to reach it. Photo by Heather Taylor on 4/22/2023.

For anyone who drives regularly, there are sights so commonplace, they are almost invisible. There are unsightly elements like roadkill and litter, or more attractive parts of the landscape such as flowering oleander, which fills the medians of many California highways. Then there are the all-too-common roadside memorials of wooden crosses and artificial flowers which dot the shoulders of roads wherever someone may drive.

I drive too many miles each week to easily calculate. I make deliveries on roads spanning three counties for work, and commute an hour and a half to attend classes. While I have long possessed a morbid curiosity about these highway monuments, I am even more aware of them with long hours in the car. As I learn more about these memorials and the stories behind them, I think they hold great value, despite their temporary nature.

Perhaps naively, I did not initially suspect these small, unassuming expressions of grief, created by family members or friends, to be the source of controversy.

There are differing opinions loudly voiced on the topic of informal roadside memorials.

The crosses or signs are not often the only item at the site, belongings such as stuffed animals or items of clothing to remember loved ones are also left behind. Faux flowers are also common, which quickly fade and become tattered in the elements, resulting in an issue of memorials being considered trash or litter.

The majority of trash on the streets comes from people improperly disposing of it less than two miles from where they purchased it. A more effective way to address issues of roadside litter may be providing more trash cans at strategic locations, instead of worrying about the occasional, stationary roadside shrine.

Another concern is safety. Family members may risk injury when installing a memorial along a busy road, and I would agree this is a valid concern. There were plenty of memorials along my routes I wanted to photograph but could not access safely.

The other safety concern often mentioned is that drivers may be distracted by the shrines and become involved in a traffic accident themselves.

In a 2019 study, Vanessa Beanland and Rachael A. Wynne said, “In general, the findings suggest that roadside memorials capture drivers’ attention at least some of the time, but do not necessarily have a large or meaningful impact on safety-related behaviors.”

An inverse argument is often made in support of allowing roadside memorials, saying the sight is a reminder for drivers to make good decisions and stay safe. While I have often thought this myself, the same study by Beanland and Wynne determined seeing crosses and flowers on the side of the road didn’t affect drivers in a positive way either.

The value of these memorials is present in other ways.

Memorials for car accidents are a relatively new phenomenon, due to the short portion of history in which people have been driving cars. However, the tradition of creating memorials or shrines along trails dates back several centuries.

Writing for the International Society for Landscape, Place & Material Culture, Jeffrey L. Durbin drew comparisons between the highway memorials of the present and roadside crosses installed along trails in Arizona in the 1700s.

“Initially, the crosses were to memorialize people who had suddenly died without having been absolved of their sins,” Durbin wrote. “Travelers would stop at the crosses and light candles or say prayers for the deceased.”

Centuries later, around the 1940s, the Arizona Highway Patrol would place white crosses at the site of fatal accidents for victim’s families.

“Today, such memorials are at the edge of busy highways and no provision is usually made for travelers to stop and pay their respects to the victims, so their use and intent have slightly evolved,” Durbin said.

Now, the value of these memorials is more deeply seated in the expression of grief for a family. A roadside memorial marks the site of a sudden, public tragedy, and it is logical that grief surrounding the event may be shown in a similar manner.

David Charles Sloan wrote about the cultural importance of roadside memorials for the Vernacular Architecture Forum.

“They suggest a deep need to perform an act of mourning that transcends the widely accepted modern process of mourning and burial,” Sloan said. “They provide public commemoration of a life lost in a society that struggles with representations of death and memory.”

Is that struggle with facing public reminders of death another reason why some people support banning roadside memorials? I believe it may be.

Seeing a constant reminder of the dangers that we face completing a mundane, everyday task like driving can be unpleasant. While a reminder of risk is sobering, it may be necessary to enact progress and change.

Writers Peter Jan Margry and Cristina Sanchez-Carretero view public memorials of traumatic deaths as more than just an expression of mourning, but also as an opportunity for protest.

“They are performative events in public spaces that often trigger new actions in the social or political sphere,” they wrote.

Margry and Sanchez-Carretero were primarily concerned with the spontaneous memorials erected at the sites of national tragedies or in memory of the death of a beloved celebrity, however they also addressed roadside memorials.

“Crosses placed at the site of a traffic accident are often also protests against drunk driving, traffic rule violations, or badly maintained roads,” Margry and Sanchez-Carretero said.

Whatever the motivation, roadside memorials are an ubiquitous and easily recognizable shorthand in our culture, plainly stating where a death has occurred.

The criticisms surrounding these shrines do not outweigh the value they hold for the families of the dead, and they will not likely stop them from continuing to create memorials at the site where their loved one was last alive.

Some passersby even find beauty in these makeshift monuments, like photographer Sarah Lyons.

Lyons created a photo series called “Last Alive (Roadside)” in which she documents roadside memorials.

“Many elaborate and others spare, these visible tributes are evidence of evolving grief rituals particularly for those who have experienced an abrupt loss,” Lyons said. “And, the loss of my father in a highway accident makes the work a personal meditation on impermanence, immortality, and faith.”

I know when I drive by a roadside memorial or catch a glimpse of one in the distance, thoughts of mortality also come to my mind. And I, for one, drive slower and take a bit more care on the corners with the white crosses.

Heather Taylor can be reached at [email protected].