The ongoing drought has kept Lake Oroville nearly 20 percent below its average capacity for this time, according to the Department of Water Resources’ website, causing its power plant to produce only half the electricity it should be.

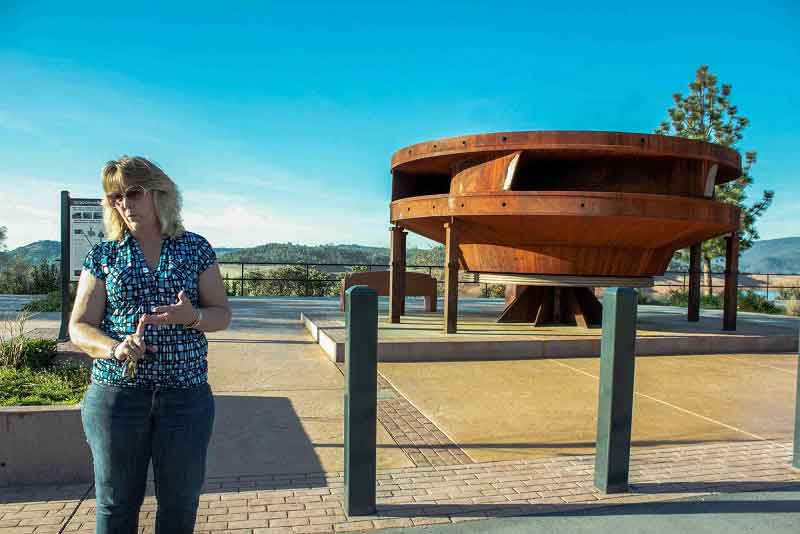

People don’t use much power during the winter, so this energy shortage hasn’t affected off-campus students and Chico residents yet, said Jana Frazier, the facility’s tour guide.

However, those who stick around in the summer may feel the impact if skies stay sunny.

Summertime in Chico means air conditioners on blast, sometimes all day, Frazier said.

The hottest day in Chico hit 111 degrees last year, according to WeatherSpark.

These high temperatures will attract high electrical consumption, but Lake Oroville could be even lower by then.

“We’re kind of expecting this summer that we’re going to have some power outages in the state,” Frazier said. “The drought is affecting any aspect of every person’s life.”

This drought has left Lake Oroville lower than the drought from 1976 to 1977 did, according to the Department of Water Resources’ website.

A 1976 drought left hydroelectric energy low and electricity expensive because of increased oil and natural gas dependence, according to a 2011 U.S. Department of Energy study. The same happened during a 2001 drought.

Though the study barely mentions a drought that occurred from 1986 to 1992, California hydroelectric production plummeted then too, according to the California Energy Commission.

The Hyatt Power Plant at Oroville Dam currently is producing around 511 megawatts a day with only one turbine running, Frazier said.

The plant can produce up to 853 megawatts a day with a full lake and all six of its turbines running.

The dam’s unique system creates power through the spinning of turbines, which spin from water falling through the intake system and into them, Frazier wrote in an email to The Orion.

Dams run on water horsepower, said Steffen Mehl, a Chico State associate professor of civil engineering.

This power depends on the flow, or volume, of water moving through the system and the height the water falls from, he said.

In Oroville’s case, both are affected by the drought. The plant can’t flow too much water out or it risks drying the reservoir if the same amount of water isn’t flowing in.

The lake’s low elevation also eliminates the height needed for the drop to spin the turbines for optimum energy production, Frazier said.

“The lake looks like a giant mud puddle,” Frazier said, “So all that space would normally be filled with water and normally drop into our intake system and fall into our turbines to spin our electricity system.”

The dam outsources its electricity to California’s grid, which distributes electricity throughout the state. Pacific Gas and Electric Company draws energy from the grid, so it relies on the dam’s hydroelectric power.

PG&E; is Chico’s only energy provider, said Mark Orme, Chico assistant city manager. As far as he knows, the city can’t purchase energy elsewhere because no one else has asked to sell it.

However, even with California losing its hydroelectric power during this drought, early anticipation, coordination, planning and a public relations campaign to promote conservation efforts succeeded for past droughts, according to the 2011 Department of Energy study.

Frazier agrees.

“We can make this work even though we have no water,” she said. “If everybody practices good conservation, we’ll be fine — and that might be flushing your toilet every second use, as gross as that sounds.”

Yessenia Funes can be reached at [email protected] or @theorion_yfunes on Twitter.